Growing College Success from First Semester Failure

Last September, a new cadre of freshmen began college haunted by a looming statistical trend: More than forty percent of those who have ADHD were destined to fail their first semester. And after this initial failure, only a portion will attempt another semester, and fewer still will go on to complete college on schedule.

Last September, a new cadre of freshmen began college haunted by a looming statistical trend: More than forty percent of those who have ADHD were destined to fail their first semester. And after this initial failure, only a portion will attempt another semester, and fewer still will go on to complete college on schedule.

For those brave students who persevere and return after winter break, the beginning of the second semester represents a perilously critical time for self-reflection, new skills acquisition, and growth. Without this progress, scholastic probation turns into scholastic suspension.

These aren’t marginal students who’ve managed to slip through the college vetting process. In fact, they are intelligent, motivated students scrutinized by rigorous standards of entrance exam scores, grade point averages, extracurricular activities, as well as their ability to convey these accomplishments in essay and interviews.

So, what causes these students—who gave every indication they are bound for success—to fail? What are the common denominators of their failure? And, most importantly, what can be done to redirect them toward success?

What do they need?

Typically, these students lack life skills that weren’t fully developed in high school or have not yet transferred into the less structured and more challenging setting of college. Executive functions and emotional intelligence top the list of greatest deficits.

Learning to organize themselves to function independently, perhaps for the first time in their lives, can prove problematic in the chaos of developmental, emotional, psychological, and social change while they also struggle to adjust to a completely different education system.

This chaos is only exacerbated when they leave home with untreated issues like anxiety, depression, gaming addiction, or substance abuse. College becomes little more than a newer, less structured, and even freer environment for these difficulties to fester even further. For those undiagnosed, ADHD makes its first appearance as they enter an environment that requires more effort and sustained focus—a place where simply relying on native intelligence is not enough.

Burdened by this lack of skills and resources, students often find themselves alone in an uphill struggle to succeed in the current semester, while also learning the important “how to do it” lessons that will enable them to succeed in future semesters. College rarely offers students with ADHD a template or model to hit the ground running so that they can learn and grow from the inevitable mistakes they make due to these deficits. Yet those who fail the first semester—as well as those who pass by the skin of their teeth—are more likely to keep trying and improve when they have a such a model.

They need structure

Beyond off-the-shelf ideas, like going to office hours, using a calendar/planner, asking for help, using their accommodations, these students need a structure that will empower them to better organize themselves around the deficits that accompanied them to college and to experience struggle (and even occasional failure) as an integral and useful part of the learning process.

A few principles need to guide this structure:

- Students with ADHD tend to fail (and succeed) in recurring patterns. Signs or indications of these patterns emerge early in the semester.

- Students need to learn to identify and make use of these patterns.

- Understanding patterns and indicators will help them self-monitor—to know when and specifically how they are trending toward success or failure. From here they can develop a plan that serves as an early warning system for failure.

- They can use this early warning system—along with a pre-developed plan of action—to reinforce successful behaviors or interrupt those leading toward failure.

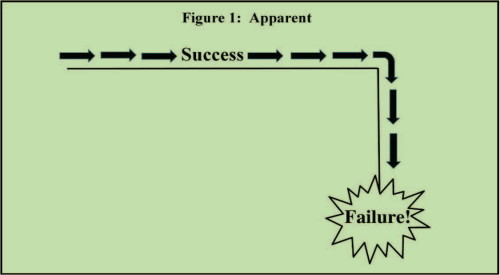

Here’s what this model looks like when taken from theory into practice (Figure 1). From the outside looking in, failure emerges—seemingly out of nowhere—near the end of the semester, where students and parents are equally startled by its abrupt appearance. By outward indications, it may have seemed as though the student had been doing well up to that point.

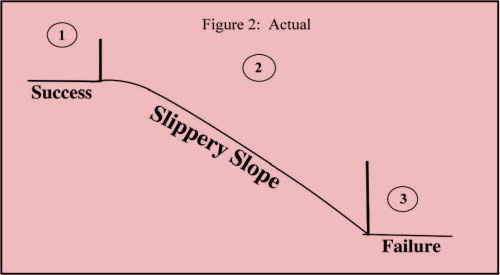

But seen from the inside of the process, the real picture of failure is more like Figure 2, where indications of failure were evident (but unobserved) early in the semester. And the process of moving from success (zone 1), down the slippery slope (zone 2) continued uninterrupted until failure was a logical conclusion (Zone 3). Let’s take a closer look at the zones.

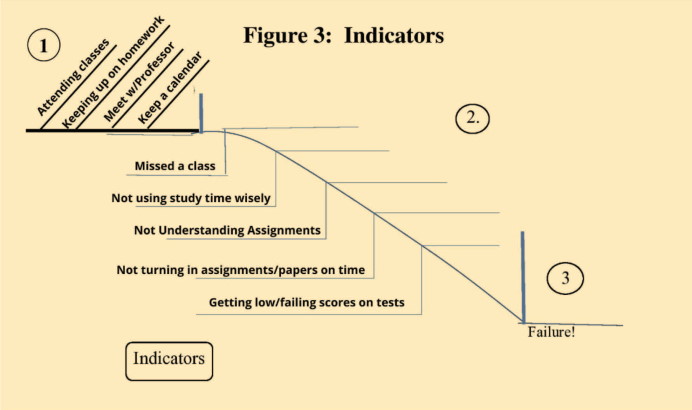

Students typically begin the semester in Zone 1, where they are practicing successful behaviors and getting successful results—like regularly attending class, timely completion of assignments, and balancing academic and personal life. As Figure 3 illustrates, the drift into Zone 2 is evidenced by subtle to increasingly evident and intensifying indicators. For example, an occasional missed class and poor preparation for a test increasingly becomes the norm of infrequent attendance, never preparing for, and consistently failing tests. In lieu of productive work, students fill their life with socialization, gaming, or other means of coping with the resulting anxiety and depression. Zone 3 is the point at which no action can reverse the slide to failure. Here students are left to either withdraw (if not too late), quit, or outright fail.

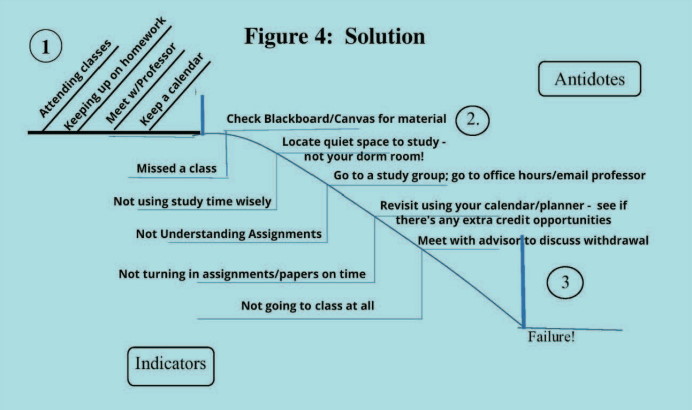

Figure 4 illustrates some possible antidotes to typical indicators of slide toward failure. Because both the indicators and antidote behaviors are subjective and personal, the individual self-reflective work of discovering these patterns and solutions requires endeavor unique to each student and typically leads to discoveries in areas like motivation, organization, and self-advocacy.

For each indicator, a student can devise an antidote behavior that will get them back on track for success. However, as Figure 4 demonstrates, the further down the slippery slope of Zone 2 the student slides, the more intense and complex the antidote behavior required to restore to successful behavior. And as they move further down the slope, they face increasing levels of stress, anxiety, and depression in addition to the burgeoning load of unfinished work. The resulting downward momentum contributes to the rapid onset of irreversible failure and the shock accompanying this awareness.

Developing a personalized Success Curve

The model presented here and its accompanying terminology offers a unique language to express the subjective nature of this experience and provides a structure for plugging into the process. For example, during academic coaching sessions, our students will check in with “Here’s where I am on the Curve” and “This is the action I will take to get back to or stay in Zone 1 (success).”

Doing the work of developing a personalized Success Curve before the semester begins provides students a better chance of conceptualizing, anticipating, and averting the dangers of the slippery slope of Zone 2. This charted visual of their Curve offers a functional tool for identifying, celebrating, and reinforcing successful behaviors in addition to noting and remediating actions that could lead to failure. As students become proficient in the use of this model, they find ease in applying it to other aspects of college life that need monitoring as well, such as emotional hygiene, social life, self-care, and life balance.

Doing the work of developing a personalized Success Curve before the semester begins provides students a better chance of conceptualizing, anticipating, and averting the dangers of the slippery slope of Zone 2. This charted visual of their Curve offers a functional tool for identifying, celebrating, and reinforcing successful behaviors in addition to noting and remediating actions that could lead to failure. As students become proficient in the use of this model, they find ease in applying it to other aspects of college life that need monitoring as well, such as emotional hygiene, social life, self-care, and life balance.

College success for students who have ADHD is a complex process that goes beyond simply making good grades and passing. These students require heuristic and malleable tools to develop the self-awareness and management necessary to create healthy responses to adversity. Models such as the one presented in this article offer students the opportunities they hunger for to fully encounter their limitations, challenges, and failures, and mold them into tools that provide roadmaps for success in college as well as the world of work beyond.

Jon Thomas, EdD, LPC is founder and president of The ADHD College Success Guidance Program. He is a counselor, educator, writer, and author of Thriving at the Edge of Chaos: Making ADHD a Superpower in College and Career.

Jon Thomas, EdD, LPC is founder and president of The ADHD College Success Guidance Program. He is a counselor, educator, writer, and author of Thriving at the Edge of Chaos: Making ADHD a Superpower in College and Career. Pamela Barton is CEO of The ADHD College Success Guidance Program, where she also serves as director of student services and provides academic/life coaching and college readiness training.

Pamela Barton is CEO of The ADHD College Success Guidance Program, where she also serves as director of student services and provides academic/life coaching and college readiness training.