How to Deal with Situational Variability

Attention Magazine August 2021

How to Deal with Situational Variability in Adults with ADHD

YOU HAVE BEEN SUCCESSFUL at your job for years, but struggle with it now because you are working from home. You can plan and execute all the elements of a large project, but have difficulty planning a trip. Your child can design and code the most elaborate computer games, and yet has trouble completing simple math assignments. These inconsistencies in performance are one of the most confusing aspects of having ADHD. David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue Airways, sums it up with, “I have an easier time planning a twenty-aircraft fleet than I do paying the light bill.”

YOU HAVE BEEN SUCCESSFUL at your job for years, but struggle with it now because you are working from home. You can plan and execute all the elements of a large project, but have difficulty planning a trip. Your child can design and code the most elaborate computer games, and yet has trouble completing simple math assignments. These inconsistencies in performance are one of the most confusing aspects of having ADHD. David Neeleman, founder of JetBlue Airways, sums it up with, “I have an easier time planning a twenty-aircraft fleet than I do paying the light bill.”

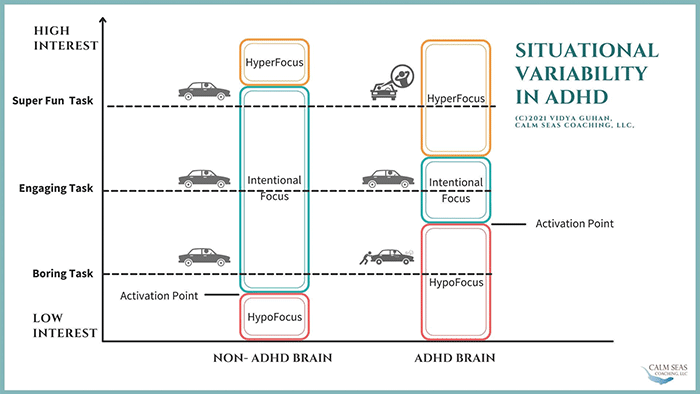

The short answer for why these inconsistencies occur is “situational variability.” ADHD comes with strengths and challenges, and which of these is more at play is influenced by the situation or context. Without understanding how the ADHD brain is fundamentally wired and the implications of this wiring, it is very easy to think that your loved one with ADHD “could do it if they wanted to” rather than realizing that they “would do it if they could.”

Typically, for someone with ADHD, when a task or activity is of high interest to them, they feel energized, motivated, and able to easily engage and perform at a very high level. But, when the task or activity is of low interest—even if it is important, simple, or short—they find it viscerally painful and almost impossible to engage with.

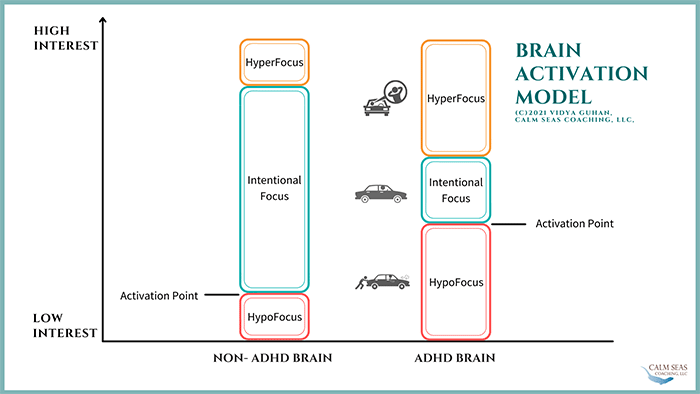

Why? The human brain needs dopamine, a neurotransmitter that facilitates communication between neurons, to be fully activated or “switched on” so that it can do its job; that is, pay attention, focus, and self-regulate. Dopamine levels in the brain are positively correlated with our level of interest in a task.

If a task is inherently boring to someone with ADHD, dopamine levels are so low that their brain is unable to “activate” to do the task. They can’t pay attention even if they want to. They are in a state of hypofocus. This is like trying to move a car when the engine is turned off—the car needs to be physically pushed. A client describes the perceived effort in trying to engage in a task when in hypofocus as “pushing the car uphill while hopping on one foot!”

However, if a task is extremely interesting and stimulating to people with ADHD, they can lose track of time and place and stay absorbed in the activity for hours. They are unable to disengage from the task. This is a state of hyperfocus. This can feel like being in the zone, where the car is now self-driving and there is very little perceived effort required to carry out the task. This is an ADHD superpower!

The sweet spot between hypofocus and hyperfocus is what I call the intentional focus range. In this zone, tasks are interesting enough to capture the ADHD brain’s attention, and they can engage purposefully and by choice. Now, the car’s engine is turned on and they are in the driver’s seat, taking charge of when to start or stop a task, what they want to do, and how they want to do it.

The range of hypofocus and hyperfocus is much greater for someone with ADHD than for someone without ADHD, while the “sweet spot” is much smaller. This leads to greater situational variability for someone with ADHD.

Here are some ADHD-friendly strategies that help you adapt to four different situational contexts: high versus low interest, strengths versus challenges, structure versus flexibility, and positive versus negative environments.

High versus Low Interest

Tasks that are genuinely interesting are easier to engage with, while tasks that are boring are not.

- Engage with areas of genuine interest and passion wherever possible.

- Instead of asking yourself, “How can I make myself do this boring task?” ask, “How can I make the task more interesting or activate my brain for this task so it is easier to do?”

- Do something fun before you do the boring task.

- Add something interesting to the task. For example, play some music in the background while working, listen to a podcast while cleaning, or watch TV while folding laundry.

- Make your prompts and reminders attractive to you. Explore different mediums and colors.

- Incentivize or reward yourself immediately and frequently as you work through a bigger task.

- Gamify the task in some way. For example, create timed games, point systems, competition, and challenges.

- Add humor and play to the task in some way.

- Body double with someone or connect with others (for example, join a group or take a class).

- Add novelty and variety and change things up frequently so they stay fresh and interesting.

- Get some exercise or get outside in nature. A brisk walk and shared laughter with a friend can do wonders for an underactivated brain.

Strengths versus Challenges

Situations that play to our natural strengths are more likely to lead to success.

- Become aware of your strengths, passion, values, processing styles, and talents.

- Explore situations and contexts in the past where you have been successful. Projects that you loved or were easy for you, or experiences that made you happy or feel really good about yourself, can show you who you are and how you are naturally wired for success.

- Select tasks and activities that are a good fit for your natural strengths and preferences where possible.

- Leverage your strengths and incorporate them into any task. For example, if you know that you are a hands-on person, you may do better with a paper planner, white board, or Post-it notes to keep track of your tasks. If you are a verbal processor, speak to someone, record yourself or use a voice-to-text app to capture your thoughts and organize your information.

Structure versus Flexibility

Finding the right balance of structure and flexibility can help you get things done in a given situation.

- Create sufficient structure to be successful with enough flexibility so you do not feel restricted or deprived.

- Use timers, reminders, routines, automation, and accountability to keep track of schedules and progress. This will give you clarity on what to do, how to do it, and when to do it.

- Give yourself adequate time for creativity and to recharge your batteries to avoid the internal pushback of being “made to do something.”

- Set sufficient boundaries so that you can capitalize on your peak performance windows. For example, make yourself unavailable on your calendar, silence your phone, or turn off notifications when working on a project.

Positive versus Negative

We tend to thrive in positive environments and shut down in negative ones.

- Pay attention to positive feedback, encouragement and your strengths as this can activate your brain and energize you emotionally for the tasks at hand. This is true for both external feedback and self-talk.

- “Make friends” with feedback by reframing it as an opportunity for growth, a learning opportunity, or a pathway to success. When looking at written feedback, try highlighting all the positive feedback and reading those first.

- Become aware of any self-defeating self-talk and replace it with more empowering self-talk. For example, if you catch yourself saying “I don’t want to” or “I can’t handle it,” try saying “I am willing to do the first step” or “I can handle it for ten minutes” instead.

- Build a robust support system for yourself including a cheerleader, venting buddy, sidekick, mentor, coach, helpmate, playmate, your rock, emotional support animal, and so on. This gives you the outside help to build resilience and counter negativity when you are faced with it.

- Keep a gratitude or success journal to help you shift your attention back to the positive when you need a boost.

Good internal self-care habits

Apart from these external contexts, there are internal elements of good self-care that directly impact our functioning from day to day. Healthy habits around sleep, exercise, nutrition, medication management, mindfulness practices, and social connection make it easier for your brain to regulate well. Build routines and structure for consistency in these areas to minimize variability in how you feel and perform from day to day.

The pandemic has shaken up our environment, our structures, and our routines. For many people, this amplifies the challenges they face because the new structures (like working from home with fewer face-to-face interactions) are not aligned with their strengths and interests. Although they may not have control over the situation they are in, approaching it with an understanding of the wiring of the ADHD brain and using the strategies discussed above can help empower them to thrive.

Vidya Guhan is a master certified ADHD coach with the Professional Association for ADHD Coaches, a professional certified coach with the International Coach Federation, an ADD Coach Academy certified coach graduate, and a licensed speech pathologist. She is the founder of Calm Seas ADHD Coaching and serves as the co-president of PAAC. She helps adults with ADHD improve their executive function skills and become self-empowered to achieve their personal and professional goals. She is a well-received speaker and offers webinars on ADHD-related topics. Her signature course is Procrastination to Productivity! 6 Essential Executive Function Skills to Start, Do and Finish Tasks, where participants learn her unique ACT NOW© approach. Learn more at

Vidya Guhan is a master certified ADHD coach with the Professional Association for ADHD Coaches, a professional certified coach with the International Coach Federation, an ADD Coach Academy certified coach graduate, and a licensed speech pathologist. She is the founder of Calm Seas ADHD Coaching and serves as the co-president of PAAC. She helps adults with ADHD improve their executive function skills and become self-empowered to achieve their personal and professional goals. She is a well-received speaker and offers webinars on ADHD-related topics. Her signature course is Procrastination to Productivity! 6 Essential Executive Function Skills to Start, Do and Finish Tasks, where participants learn her unique ACT NOW© approach. Learn more at