Understanding Meltdowns: The ADHD Volcano Model

A MELTDOWN CAN SEEM TO COME OUT OF NOWHERE. It’s one of the challenging or explosive behaviors we see in those who have ADHD. Sometimes it appears as poor self-esteem, yelling, rage, or tears. But sometimes the challenging behavior is your own in reaction to your spouse, child, sibling, or friend who has ADHD: “Why did they not hear me? Now I’m the angry one.”

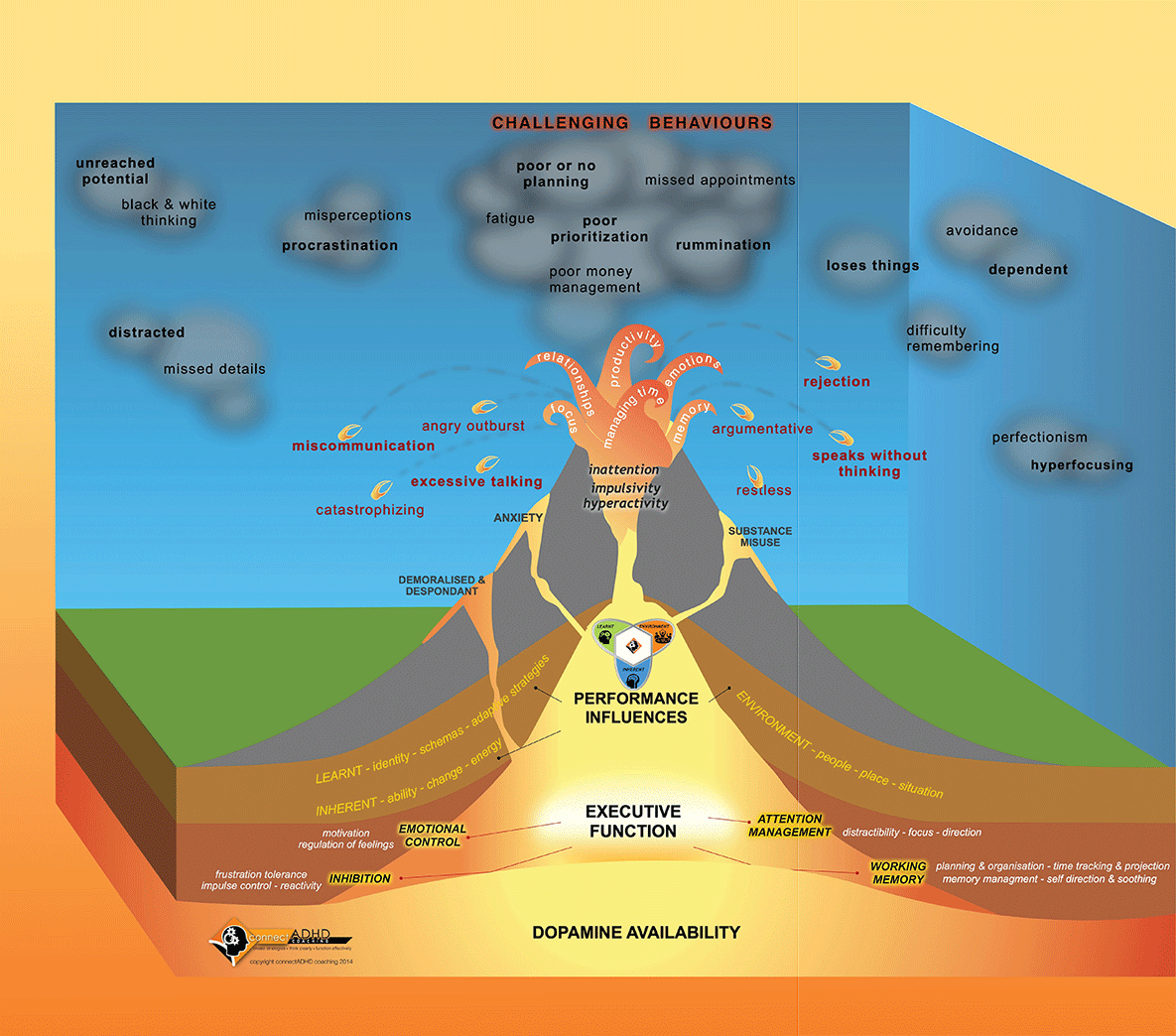

The Connect ADHD Volcano model has been developed to explain and create understanding of these challenging and explosive behaviors. It is an educational model that represents the relationship between observable behaviors, diagnosis, core symptoms, and the underlying factors of performance influences, executive function skills development, and how neurochemistry underpins all of these layers.

What is underlying these challenging or explosive behaviors? When a person experiences challenges fitting in or struggling with getting through the day, there can be numerous reasons. Behaviors that don’t fit in with what is expected as the norm are often more than just behaviors. They can be messages and information that something is not as it ideally should be.

Looking at the top of the Volcano we see examples of behaviors that are common with ADHD. Procrastination, emotional outbursts, black-and-white thinking, perfectionism, chronic lateness, distractibility, and hyperfocus are but a few.

Some people may question, “Doesn’t everyone feel like this sometimes? Is it really ADHD?“

Seeking diagnosis and clarity

When ADHD is present, it can make daily life difficult to manage and may create the perfect storm for a stressful experience. Their symptoms may cause such angst that people will seek help from health professionals. Their behaviors can cause poor performance outcomes, negatively impact self-esteem, and seriously affect relationships. In the long term, ADHD can limit potential and opportunities both personally, academically, and professionally. Unfortunately, ADHD-related behaviors can often be judged very harshly, especially at school or in the workplace.

Seeking professional help and uncovering a diagnosis of ADHD can be life-changing in a positive way. It can also be very confusing and difficult to process, especially when the individual does not come from a medical or educational background. The terminology can be overwhelming.

A vast supply of information is available based on neuroscience, but there is also an abundance of myths and misinformation. It can be hard to know where to start looking. Good information and understanding are key to moving forward in a positive direction.

As ADHD and EF coaches and educators, we developed a tool to help clarify this complex disposition. In one easy-to-understand model, the Connect ADHD Volcano breaks down and clearly demarcates:

- observable behaviors at the top

- the diagnosis terminology—core symptoms and some coexisting conditions

- underlying factors, performance influences, and the executive function skills layer

- neurochemistry at the base

Observable behaviors

It is very common for our clients to look at the behavior section of the Volcano and say, “Yes, I have all of those!” Not every client will have all the behaviors noted, but most will have many. The types of behaviors that we typically see are displayed at the top of the Volcano, including frequent or chronic lateness, poor time management, being lost in time, rumination, procrastination, negative self-talk, black-and-white thinking, catastrophizing, talking too much and interrupting people, not finishing tasks, losing valuables, fidgeting, drifting in conversations, and day dreaming.

These types of behaviors indicate that the person’s skills are at this point not fully developed and therefore, not fully regulated. Inconsistent outcomes result and can lead to socially unfavorable events, where the person’s mind and body responds either physically (often slamming doors or lashing out) or emotionally.

Russell Barkley, PhD, says that to view ADHD as a person’s being easily distracted or impulsive only trivializes ADHD. We must look at the impact of executive functions.

Joseph: A Case Study

Fourteen-year-old Joseph was running late for school again and missed the school bus. He lost track of time. The television was on, and there was a news story about the Pokémon craze. His parents had already gone to work, so he had to catch a much later bus and arrived at school late. One of his classmates made a joke when he arrived late, and Joseph had a meltdown in front of the whole class. He turned over a table and received a detention.

Joseph has ADHD, not as yet diagnosed. This scenario demonstrates deficits in some key executive skills. Attention was challenged by his being distracted easily by the television. Inhibition was challenged when he was unable to ignore the Pokémon story. His challenges in emotional regulation showed in a lack of motivation to get to school and his heated outburst, and his working memory challenges were revealed with regard to tracking time and tasks to direct his self-talk to getting out of the door, on the bus, and successfully arrive at school on time.

Diagnosing coexisting conditions

The diagnosis of ADHD has itself been a topic of confusion in the past. The “Is it ADD or ADHD?” discussion still continues in the general population. It is not uncommon for ADHD in women to be overlooked, and instead they are diagnosed with anxiety or depression—which may also occur alongside ADHD or as a result of ADHD being in that person’s experience. Males and particularly females may be overlooked if their symptoms fall into the more inattentive presentation of ADHD. Inattentive symptoms can be almost invisible and not become apparent until unpleasant or even damaging outcomes are evident.

It is well documented that ADHD rarely travels alone. This means that about 40-80 percent of people with ADHD will have one, two, or even three co-occurring conditions. These often fit into two categories—mood disorders such as anxiety and depression, which are quite separate to the anxiety or feelings of anguish that occur as a result of ADHD. Sometimes conditions such as bipolar disorder also present in the individual. Other common co-occurring conditions are academic in nature, such as dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia. This is shown in this diagram as the two other volcanos in the background of the ADHD Volcano.

Performance influences and neurochemistry

There are other factors that influence a person’s conduct and therefore ultimately affect their behavior. These influences include their inherent disposition, environment, and learned experience.

- Inherent pertains to the way that we think, our cognitive capabilities, our disposition regarding our neurochemical balance, and how motivated we are toward tasks.

- Environment relates to what is happening to the people (including self), the physical area of the environment and the nature of the task at hand. Is the task critical, stressful, and imminent; or is the task a long way away and hard to envision?

- Learned experience is what we have learned or thought in the past that can affect the way in which we function in the present. There can be a predisposition for strong negative thoughts in the presence of ADHD.

Executive function skills development is key in the process of successfully managing one’s self in the present moment and toward the future. The Volcano links challenges with executive functions as the basis for inconsistent or irregular outcomes of behaviors. The following executive functions are key:

- Response inhibition. Challenges here affect having a thought filter in place.

- Emotional regulation. Deficits affect motivation, unregulated highs and lows, and outbursts.

- Attention management. Deficits affect distractibility, hyperfocus, and the ability to shift attention when needed.

- Working memory. Deficits cause forgetfulness, planning and organizing issues, time awareness issues, problems with self-directed talk, and challenges with task management.

Current research also indicates that people with ADHD have may have up to a 30 percent delay in their executive function skills in comparison to their peers of the same chronological age. This can explain why when we send our eighteen-year-old children to college, their planning and other executive skills function more like those of a twelve-year-old. Their actions and planning challenges are not intentional; they are the outcome of ADHD.

Once these key executive function skills are assessed and analyzed in terms of success or deficit, appropriate strategies can be developed and change can be implemented to support the individual. Once we are attuned to the fact that the person needs specific skill development, we then have the information we need on how to develop that skill. These behaviors are clues to important information. The challenging or explosive behavior are our markers to where we have the opportunity to build and improve skills.

The base of the Volcano demonstrates the deep and foundational involvement of the neurochemistry of the brain and how it impacts all the layers above the Volcano. Insufficient availability of the neurotransmitters, dopamine and noradrenaline, may cause an imbalance to all the layers above, starting with executive function, performance, diagnosis, and ultimately behavior. All of the impacts are based in brain chemistry and underdeveloped skills—and not a character flaw of the individual with ADHD.