Principles for Parenting a Girl with ADHD

Attention Magazine December 2022

Parenting matters. This might appear to contradict what we know about the causes of ADHD in girls (and boys). Please let me clarify. No, how you parent your daughter doesn’t cause the disorder. But parenting does contribute greatly to outcomes for girls with ADHD. Despite the biological realities underlying ADHD, parenting practices are essential to changing the trajectory for your daughter and her condition.

How parenting contributes to a happy, healthy future for your child and exactly what to keep in mind to promote your daughter’s welfare is the focus here, where I will present current science related to the essential concept of parenting. I’ll explain the fundamentals of parent–child attachment and analyze the main dimensions of parenting behavior—responsiveness/warmth and control/demandingness. I’ll also get into other key parenting practices of real relevance as your daughter gets older: monitoring, consistency (within a given parent and between parents), and “fit” (that is, the realignment of parenting philosophies to different children).

How parenting contributes to a happy, healthy future for your child and exactly what to keep in mind to promote your daughter’s welfare is the focus here, where I will present current science related to the essential concept of parenting. I’ll explain the fundamentals of parent–child attachment and analyze the main dimensions of parenting behavior—responsiveness/warmth and control/demandingness. I’ll also get into other key parenting practices of real relevance as your daughter gets older: monitoring, consistency (within a given parent and between parents), and “fit” (that is, the realignment of parenting philosophies to different children).

Attachment

Let’s begin at the beginning. When a baby is born, and even before (during the prenatal period), most parents have real hopes and expectations of forming a close relationship with her, full of responsiveness and care. On the other hand, for a host of difficult reasons—general life stress, family crowding, problematic issues in early relationships with their own parents, or competing economic or psychological needs—some parents may not be as available and responsive as the baby or young child requires.

Overall, the quality of the bond between a newborn and her parent is termed attachment. Furthermore, it’s not just in the first months or even years of life that the attachment bond is important. Close attachments are essential across the life span.

Babies are completely dependent on their caregivers for survival. Don’t think, though, that young children are simply passive recipients of inputs from their environments. Instead, babies differ from one another in their basic, bio- logically driven ways of showing emotions and behaving in the world (some- times called temperament). And they are active observers and synthesizers of what they perceive in terms of safety and security, well before they can talk. Indeed, babies have a kind of “sixth sense” about how responsive their parents are during the crucial early months of development.

Let’s take a broader view. Secure attachment bonds are essential for any primate species, particularly humans. After all, primates are typically not as large, strong, or fast as potential predators. And primate babies need long periods of development during which they must (1) be kept safe and (2) learn the essential skills necessary to survive and thrive. Human babies, in particular, need to learn, from families and cultures, the many cognitive and socioemotional strategies needed to thrive and contribute to their community.

During the early days and months of life, babies put out distress calls when their needs are overwhelming. It’s hard to think of a stronger tug on your heartstrings—or patience—than the piercing sound of an infant’s cries when hungry or tired. Simultaneously, parents are particularly attuned to respond to those signals. Thank goodness (and natural selection) that nearly all adults see babies as adorable. In other words, especially if the baby is ours, we feel closely bonded to them, especially when social smiles emerge at a few months of age. Without all this, no humans would be around today. The youngest members of our species require huge amounts of attention and regular, sensitive caregiving. Not “perfect” amounts—no parent can be superhuman—but regular and adequate.

Although most parents provide ample comfort and nurture to their infants and toddlers, yielding a secure parent–child attachment, others may not be as able to do so. Babies sense such ambivalence and distance. Over time, young children with insecure attachments are less likely to actively explore their growing worlds—and may be at risk for problems in social relationships as they grow older, as well as for depression and even aggressive behavior.

At the extremes of a parent’s distance or negativity, there could be trauma—either neglect of core needs or instances of abuse. In some cases trauma and abuse can lead to patterns of behavior resembling ADHD. On the other hand, an insecure attachment between parent and baby is not, in and of itself, a core causal factor for ADHD.

If this is the case, why bring up the topic of attachment at all? The reason is that the strength of a bond between you and your child has a lot to do with how well your family will be able to promote the strengths of your daughter and engage in treatment with her. Indeed, interventions for ADHD (especially in childhood) rarely consist of one-on-one therapy between the youth and a counselor or therapist. Rather, the whole family needs to be engaged in ways of changing communication and interaction patterns, getting teachers and school officials involved, and supporting medication treatment if it’s prescribed. If the parent–child relationship doesn’t have at least some trust and good will, there’s a strong chance that progress will be minimal.

Strong attachment bonds form the foundation for the whole family’s support of a girl with ADHD.

For example, parent management training is one of the core evidence-based treatments for ADHD. But how can you, as a parent, deliver “positives” to your daughter (or, on the other hand, sustain negative consequences) unless you and she have an underlying connection? Before many parent management programs begin to establish reward charts or teach parents to use negative consequences like time-out for their offspring with ADHD, initial weeks are devoted to reestablishing a positive bond between parent and child. In short, limits and negative consequences won’t have a good chance of helping unless a positive connection between you and your daughter is established—or is in the process of being reestablished.

An important point to remember at all times is that, despite the nearly inevitable stresses and strains related to family interactions when ADHD is involved, searching for and relishing your daughter’s competencies, working on strengths rather than dwelling on weaknesses, and forming a stronger family bond are crucial parts of effective treatment.

Think of it this way: Your daughter with ADHD may well have been, in her initial months of life, more intense, or less attentive to you or others, than other babies (including her siblings if she has any). It may have been more difficult for you, as her parent, to experience the same consistent bond that you did with your other children, because she was just, well, more difficult. Her brain development across childhood and adolescence may well be slower than that of other children. It may be harder to maintain a close bond with a child who doesn’t display the easygoing temperament or timetable of maturation that many other babies, toddlers, and children display.

Authoritative parenting is marked by a “firm, yet affirmative” set of parenting practices.

But it’s never too late to work on regaining a sense of attachment security with your daughter (or son) with ADHD. Research shows that even in the presence of insecure attachment bonds early in life, once parents can “get their acts together” to become more stable sources of support, receive therapy themselves, or regain stability at home, more secure bonds can emerge. These predict better life outcomes. In fact, working toward a responsive bond is still crucial even when your daughter is a teenager and beyond. Given the long period of human development into maturity, it’s worth the hard work involved to forgive, understand, reframe, and seek out and cherish the moments of closeness that can truly help with efforts toward change, despite periods of frustration that can be part of the picture.

As highlighted below, kids and teens with ADHD have a real penchant for annoying (or at least testing the patience of) teachers and peers (as well as their parents!). This is all the more reason why you, as your daughter’s parent, should work to understand her better, to accept some of her differences, and above all, to support her as she (often erratically) navigates through her classroom, with her peers, and in her wider settings to find her standing. There’s really no substitute for a caring, accepting, yet still pushing-for-positive-change parenting bond to help her weather the storms that so many girls (and boys) with ADHD encounter.

As highlighted below, kids and teens with ADHD have a real penchant for annoying (or at least testing the patience of) teachers and peers (as well as their parents!). This is all the more reason why you, as your daughter’s parent, should work to understand her better, to accept some of her differences, and above all, to support her as she (often erratically) navigates through her classroom, with her peers, and in her wider settings to find her standing. There’s really no substitute for a caring, accepting, yet still pushing-for-positive-change parenting bond to help her weather the storms that so many girls (and boys) with ADHD encounter.

Parenting Styles

As children mature, there are countless tasks that parents must perform, countless emotional reactions and responses that parents display (and model for their children), countless interactions with teachers/schools and in the neighborhood, and countless situations that require limits and/or discipline.

For many decades scientists have tried to organize the multitude of parenting attitudes, emotional responses, and practices found in families around the world into fundamental types or dimensions. Across many cultures, two core aspects have emerged from compiling and analyzing hundreds of relevant studies.

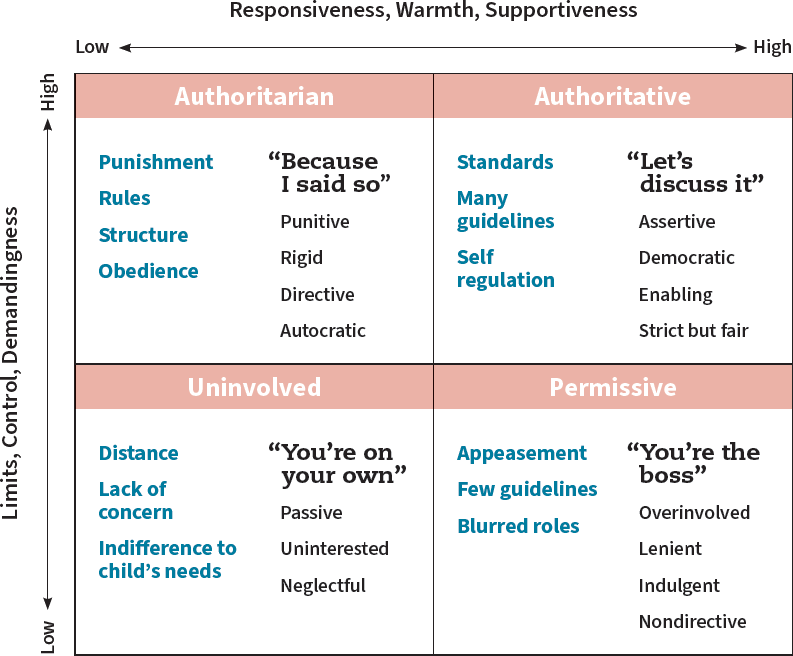

Chart of the Two Key Parenting Dimensions, with Four Parenting Styles

Two Fundamental Dimensions

Responsiveness/Warmth

First, parents fall on a spectrum related to their sense of connection, including responsiveness and warmth, with their child. Also involved here is their fundamental acceptance of the child. On the extreme low end of this dimension, parents may even wish that the child had not been born: They show little if any warmth and may even be hostile toward being that child’s parent. On the high end, parents seem to burst at the seams with joy over having this child—and work toward accepting the child’s growth as well as appreciating and loving the act of being her parent. Imagine that this dimension, typically called responsiveness/warmth, is a horizontal axis, on which the underlying feelings, attitudes, and behaviors grow steadily stronger, moving from left to right. The chart shows this dimension as the horizontal x-axis.

You might pause for a moment and appraise where you believe you fall on this dimension. Regarding your daughter, were you and are you still joyful over having her in your life? Do you still relish her new discoveries, with your sense of good will toward her sufficient to overcome the inevitable challenges of parenting? Do you let her know, through praise, hugs, and expectations for success, how you feel? Or were things difficult enough, back when she was born, that you perceived her as a source of strife or problems? Alternatively, has your initial enthusiasm given way to frequent frustration, regret, and pessimism, above and beyond day-to-day ups and downs? Does it feel as if the majority of interactions between you two are argumentative, hostile, or sarcastic?

Sometimes it’s helpful simply to list the ways in which you show (or would like to show) warmth to your daughter. A plethora of physical affection might, over time, give way to high-fives, or points on a reward chart, or more subtle indicators of the pleasure you find in parenting her. Many overt and more subtle means of showing your daughter how much you value and even treasure her exist.

Control/Demandingness

The second core dimension pertains to the amounts of control, demandingness, authority, and limit setting in which a parent engages. Imagine, here, a vertical axis, the y-axis in the figure. At the extreme bottom end of this continuum, parents apply virtually no limits at all—the child is essentially left to mature on her own. As the scale goes up, so does the parent’s sense of being a clear authority figure, with use of regular expectations and demands for behavioral control and compliance. At the very top, parental authority is absolute, with a fully regimented structure.

Again, pause to assess where you might fall on this spectrum. Do you subscribe to the philosophy that too much structure might stifle your child’s spontaneity and creativity? You might also be relatively low on this dimension if you would actually like to be more in control but are afraid of your child’s responses—or her possible rejection of you if you imposed stronger limits. If you’re on the top part of the scale, maybe you were raised in a boot-camp manner and have come to believe that this is the safest and most direct way to guide your child: clear rules, no excuses, and clear consequences for misbehavior. Or perhaps a lapse in your limits led to an incident or lack of safety for your child, which you wish to never happen again. Or you fear for the potential dangers of adolescence, so that you have clamped down hard in terms of demands and control as time has gone on.

Of course, the older a child becomes, the more authority and control parents need to hand off to the youth. This may start with allowing a growing child to play outside and continue with allowing the child to walk to the store unattended, all the way to the adolescent issues of attending parties, dating, and the like. Still, parents vary enormously in terms of their relative placement on this dimension, regardless of the child’s age.

Four Fundamental Styles

Across the large amounts of research on these two dimensions, the usual finding is that they are unassociated. In other words, a parent’s score on the first dimension (responsiveness/warmth) is essentially unrelated to that parent’s score on the other dimension (control/demandingness). In practical terms, this means that parents who are quite similar on warmth/responsiveness may vary dramatically on authority/demandingness—and vice versa.

So, as you consider the figure once again, you’ll see that the two dimensions are, in fact, at right angles to each other. That is, there are just about as many parents in the upper right quadrant (high on both dimensions) as there are in the other three quadrants. Even more, fascinating patterns emerge when we consider the kinds of parenting—and potential effects on their child—at the intersections of these two dimensions. Following is information on the four classic styles of parenting that emerge when responsiveness/warmth and control/demandingness are considered together.

Monitoring a daughter with ADHD is essential— but it’s not likely to be effective without a strong parent–child bond.

Authoritative Parenting

Here, in the upper right part of the figure, a parent is higher than average on both dimensions, a pattern often termed authoritative or authoritative/ responsive. This style comprises a real blend of the joy and acceptance related to the responsiveness/warmth dimension and the use of structure and limits related to the control/demandingness dimension. In short, parents are clearly happy in their parenting role and overtly warm with their offspring, but at the same time, they are not afraid to set clear limits and stick to them as much as possible.

As indicated by some of the adjectives in the figure, parents are both assertive and flexible. They are more than fine with setting limits, but—importantly—they explain those limits to the child during calm conversations that are removed from the time of any infractions. In other words, the relatively high demands and control are balanced by a democratic stance, through which the child comes to understand and learn the value of the limits. The parents set the rules, but, over the course of development, the child is a growing part of those negotiations.

Many scientists and child professionals consider such authoritative parenting to represent the ideal, in that its blend of noticeable limits plus real warmth and responsiveness presents a balanced backdrop against which the child can thrive academically and socially. According to this view, such a parenting style promotes self-regulation in the offspring, which can be particularly significant to your daughter with ADHD.

Here are a few other aspects of this parenting style that can be important in raising a daughter with ADHD:

- Parents high on authoritative parenting tend to push their offspring toward independence and autonomy at age-expected times. If they base this judgment on astute observations of their child, which tell them that the child is ready, the child can benefit (especially because kids with ADHD may be several years behind their peers in overall maturation. A permissive parent (see below) may let the child or teen decide when it’s time to move up the ladder toward independence, which could be disastrous for a girl with ADHD, who is vulnerable to poor self-regulation. Authoritarian parents (described in more detail below) may actually slow the child’s independence because they tend to make most of the decisions about expectations for their offspring’s behavior. This style could rob a girl with ADHD of the extra support in developing self-regulation that she needs.

- Authoritative parents use negotiation and reasoning, rather than top- down commands (authoritarian) or the hope that the child will “see the light” (per- missive). That’s why the term democratic is often used for parents who exemplify an authoritative style. This stance may be really important for kids with ADHD, who often lack the self-regulation to control their behavior on their own but may rebel against seemingly arbitrary parental control. Engaging them in reasoning about house rules can help to “bring them on board.”

- Parents in this quadrant tend to have clear, definite views on child rearing—but not so definitive that they omit their offspring from key aspects of family decision making. As just noted, the deficits in executive function that come with ADHD leave girls with difficulty making good decisions and with planning and problem solving. Learning these important functions in the safety of the family can give them a boost.As useful as authoritative parenting can be, there are also a couple of caveats to keep in mind:

- Some children, particularly those with good self-control and reasonably stable and easy temperaments, may be easier to parent authoritatively than others. This means that no matter how advantageous this parenting style may be to your daughter with ADHD, you may find it more challenging to be authoritative with her than it was with her siblings without ADHD. Once again, the age-old chicken-and-egg question: Do parents mold their children, or do child behavioral tendencies mold their parent’s approach to them? The correct answer is “both of the above,” as parent–child interactions are reciprocal and cyclic rather than unidirectional.

- Any parent might not always be authoritative (or authoritarian, permissive, or uninvolved) and in the same ways for all children in a family. As anyone who has grown up with one or more siblings knows, parents clearly have different attitudes and expectations for different kids in the same family. So, whereas there may be some truth in assuming a parent’s general style is the same for all the children in the family, part of parenting is child-specific. In fact, research shows that the contextual factors that affect siblings differently (such as peers and child-specific parenting practices) have more bearing on later-life outcomes than those factors that affect all siblings in the same way (such as social class and general parenting styles). In short, you may need to adapt authoritative principles of parenting to your daughter with ADHD (for example, being gentler regarding some rules that are harder for her to remember but stricter on ones that might lead to danger if not followed consistently).

Authoritarian Parenting

In this (upper left) portion of the figure, the parent is high on control and demandingness but relatively lower on responsiveness and warmth. Here, there are benefits of limits but without the potential benefits of the warmth and connection of a more authoritative parenting style. This is a pattern in which parental directives hold the day. Primary here are rules, which must be followed; structure, which does not allow much in the way of deviation from such parental control; and high value placed on the child’s obedience to such rules. Punishment is a key motivator. Again, these attitudes and practices are not balanced by the more democratic stance of the authoritative parent.

On average, children growing up in homes marked by a strongly authoritarian parenting style may emerge as fairly compliant and rule following. Or, depending on their temperamental styles or the influence of many other factors, they may become defiant and rebellious, in the hope of defying or breaking down such rules. But there are few absolutes here. Some ethnic groups and cultures place a priority on control/demandingness, whereas others may favor a more democratic style of child rearing. What’s optimal in modern, 21st-century America may be less adaptive elsewhere. And many children with ADHD may recoil against a strict authoritarian parental style that’s not balanced by lots of warmth and support. In all, there are many factors that work together in shaping a child’s ultimate outcomes.

Permissive Parenting

Here we flip to the bottom-right quadrant. The parent is above average on responsiveness and warmth but relatively lower (all the way to far lower) on control and limit setting. The priority here may well be on letting the child express herself, without dragging her down into social conformity. Her authentic self-expression may well be the parent’s objective. Or, in other cases, the parent just doesn’t assert much control.

In a home dominated by this parenting style, the child will typically “call the shots” more often than does the parent. At one level, the parent may be encouraging her creativity and expression, so she can flourish. Yet at another, the parent may not appreciate the dangers of letting the child be in control as much as she is. Even more, the parent may be fearful of the child’s pushback if limits are set. Both of these issues may be relevant for a girl with ADHD, who could lack the intrinsic motivation and self-control to keep herself on track and motivated without strong support and control. Nonetheless, the parent’s warmth and acceptance, along with responsiveness to the child’s needs, are still felt.

On average (but remember, there is truly no average when it comes to parenting and child development), children of permissive parents may, if they possess good self-regulation and curiosity, thrive. On the other hand, if the child is lacking in such qualities and if the parent veers toward appeasement at all costs, even overindulging the child, the result could be a youth with little in the way of rule following, a low ability to negotiate school or engage in reciprocal relationships, or an inflated sense of self. Again, these outcomes may be particularly likely for some children with ADHD.

Uninvolved Parenting

Although there are few absolutes from the science of parenting, given huge differences across families and cultures, one is quite clear: The worst child outcomes emerge from parents in the uninvolved (all the way to neglectful) quadrant, at the lower left.

Here the parent is low on both responsiveness/warmth and control/ demandingness. For reasons of poor attachment from the parent’s own past, poverty, substance abuse, or being overwhelmed by life stress, the caregiver is neither fundamentally interested/invested in the offspring’s well-being nor able to provide more than rudimentary limits and controls on the child—at its extreme, to the point of neglect. Extreme deprivation in early development can lead to high levels of inattention and overactivity (along with attachment patterns linked to indiscriminate friendliness and other signs of extremely poor parent–child bonds). It may be the case that if you’re fostering, or have adopted, a girl with ADHD who spent early years in a neglectful environment, it would be helpful to understand some of the potential impacts on her.

Which Style Is “Best” for a Child with ADHD?

As indicated, clearly there’s a worst style—for a child with ADHD or for any child: the uninvolved quadrant, especially when it is severe enough to involve neglect. Otherwise, debate continues. Many scientists and clinicians believe that authoritative parenting most often predicts optimal outcomes, both academically and socially. It’s an intuitively appealing belief, in that the combination of warmth and structure does appear optimal for child development. Across many research samples, this in fact does seem to be the case: Kids with authoritative parents do the best, on average, in school and in peer relationships.

But it’s not that simple. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to disentangle genes and environment where parenting is concerned. A parent and their biological child share half of their genes, and those genes shape both the parent’s and the child’s behavior. So it’s hard to tell whether it’s the parenting environment—such as authoritative or other parenting style—that really matters versus the genetic similarity between parent and child. This is especially true considering that children are inevitably shaped by parenting and that parents alter their parenting style in accord with the child’s temperament or early behavior.

What the BGALS Revealed about Parenting

Our own research from the Berkeley Girls with ADHD Longitudinal Study (BGALS) project has uncovered two critical findings:

- The key variable in predicting later negative outcomes was the level of the primary caregiver’s stress and uncertainty about parenting. Noteworthy problems in school and in self-control are not typical for girls to display. So, when they appear because of ADHD, they place a great deal of stress on the family (and, I believe, actively promote tendencies for self-blame in parents). Such parenting stress—which involves feeling overwhelmed and inadequate as a parent and questioning the closeness of the interactions with one’s daughter—is a predictor of the daughter’s key impairments in later life. Anything we as clinicians and researchers can do to bolster parenting confidence and competence—and to lower parenting stress—could go a long way toward preventing the kinds of negative outcomes too often in store for girls with ADHD as they grow out of childhood.

- A girl’s report of negative interchanges with her father (but not with her mother) predicted engagement in later self-harm. This came out of a relatively recent study published by our lab, which certainly needs to be confirmed by other labs. But these findings are reminiscent of other studies highlighting the importance of fathers for girls’ development. Close bonds with a father (or father figure) may well protect girls with ADHD, in particular, against engagement in self-punishment and self-injury.

Finding a fit with the wider world can already feel like a challenge for your daughter with ADHD. Give her a good start by making sure she finds a fit at home.

Other Parenting Practices

Research has shown that parenting practices and parental stress are not the only factors that matter to outcomes for girls with ADHD. The following three additional parenting behaviors and attitudes could really matter for you and your daughter.

Monitoring and Setting Limits

It’s 11:00 p.m.: Where is your teenage daughter? This sentence captures one aspect of the important parental task of monitoring the whereabouts of a girl with ADHD.

Close monitoring is of course central to the very survival of any infant or young child. As your daughter matures, you need to promote greater independence, gradually, yet still with support and a clear sense of where she is and whether she’s safe. By later childhood, early adolescence, and later adolescence, sensitive monitoring becomes extremely important.

For girls (and boys) heading toward and proceeding through puberty, the desire for independence, the clamoring for contact with peers, and the increasing desire to keep distance from one’s parents are some of the most contentious sources of strife in family life. After all, the evolutionary “goal” of adolescence is attaining independence from one’s family of origin, procreating, and beginning the process anew. Of course, we now live in an information-based world of ever-earlier puberty paired with ever-lengthier adolescence and emerging adulthood. Little wonder that tension, arguments, and threats are rampant.

Low parental monitoring is, not surprisingly, associated with risk for associating with peers who engage in risky behavior, including substance use/abuse and delinquency. Keeping tabs on one’s children and thus being able to respond to trouble are crucial. Yet a major challenge for all families of youth this age is finding the right balance between protection and overprotection and between growing independence and “too much rope.”

All these issues are especially loaded if your daughter has ADHD, with or without additional behavioral and emotional issues. As emphasized repeatedly, she may well be delayed in her neural development and self-regulation. Her impulsivity and fragile sense of self-worth may push her toward connection with peers who can provide temporary, albeit risky, support. For now, I ask you to be aware of any tendency you may have toward looser versus tighter monitoring of your daughter as she grows up. Please consider thinking through your stance, while also remembering that appropriate monitoring is greatly facilitated by a strong bond between parent and child.

All these issues are especially loaded if your daughter has ADHD, with or without additional behavioral and emotional issues. As emphasized repeatedly, she may well be delayed in her neural development and self-regulation. Her impulsivity and fragile sense of self-worth may push her toward connection with peers who can provide temporary, albeit risky, support. For now, I ask you to be aware of any tendency you may have toward looser versus tighter monitoring of your daughter as she grows up. Please consider thinking through your stance, while also remembering that appropriate monitoring is greatly facilitated by a strong bond between parent and child.

Striving for Consistency

Consistency in parenting can take place within a given parent over time and between two or more parents/caregivers who co-parent a particular girl.

Both are important. Let’s face it: If your daughter hears you make a promise of a reward for something special that she does and you fail to deliver on it, her trust in you erodes. And if you say there will be a penalty for some misbehavior, such as failing to complete a set amount of homework or coming home too late—but don’t follow through—she learns that she can get away with such rule breaking. This pattern fuels escalations of noncompliance, along with subsequent arguing and screaming bouts at home—which benefit no one. It’s indeed hard to be consistent with your daughter with ADHD, but striving toward consistency should be a major objective.

Similarly, if parent number one is tough in terms of limits for the daughter but parent number two makes excuses and covers for her, guess which one she will turn to next time something is under dispute?

Clearly, these points look obvious on the written page—yet it’s much harder to be consistent in the real world. Being a parent (and especially the parent of a girl with ADHD, who frankly requires more consistency than most other girls) mandates soul searching, a degree of toughness, and sheer effort to follow through on your limits and consequences. And, if you’re co-parenting, it necessitates regular communication with your partner, lest one of you becomes the duped “easy mark” and the other the despised “bad cop.” Consistent, high-quality parenting 24/7 is an unreachable dream, but your daughter with ADHD will benefit greatly the more you strive toward this ideal.

Creating a Fit

The notion of “fit” has to do with flexibility and adaptability in a parent–child relationship, particularly on the part of the parent. No child can ever attain the ideal that parents might have held for her as they anticipated her arrival into the world and their home. In particular, if an infant is intense when parents might have hoped for one with a calmer temperament, they will come to realize, sooner or later, that their ability to mold and shape this temperament has real limits. As another example, some parents might not quite understand an overly placid baby when they themselves are quite vigorous.

So, beyond the parenting practices and styles under discussion here, it’s crucial that we as parents come to modify our own desires and tendencies—and appreciate our daughters’ differences, creating the kind of “space” in the family where she fits. An overused metaphor here is that it’s really hard, and typically quite unproductive, to fight fire with fire. But accepting differences, gradually building skills and competencies, and relishing your daughter’s growth in ways that you might not initially have expected, can all be of huge benefit.

What Matters Most for a Girl with ADHD?

If you look beneath and beyond your daughter’s surface behaviors, the ones stressing you out, you’ll probably see signs of her acute awareness of how often she falls short in the eyes of many people in her world. She almost certainly won’t tell you how astutely she perceives the disappointment in your eyes, her poor performance at school, her teachers’ mistrust that she’s really trying, or her classmates’ belief that she may probably be just, well, weird. Still, you might sense her self-doubt. You might notice signs of shame—which she conveys through self-denigration or anger about your limit setting—that she has failed you and herself. Such signs might include lowered eyes or doubts that she can ever repair herself enough to truly live up to your standards. These signs are often subtle, but they often serve to drive you and her into different corners.

In such cases, your daughter merits understanding and support rather than additional blame and criticism, along with a commitment from you to facilitate the skills she needs to develop in terms of self-regulation, organization, and impulse control. This endeavor starts with adopting a parenting style that tries to eliminate bickering and arguing—and follows through on demands and promises. It continues with both warmth and appropriate limits, along with the three parenting practices described above: monitoring her carefully, striving for consistency (over time for yourself and also between you and her other parent/caregiver, if there is one), and creating a “fit” for her. It also takes the realization that there are many different paths to a fulfilling future for girls like her. Finally, it includes the following tasks:

- Engaging and reengaging with your daughter and seeking out her strengths—in short, showing her your warmth and acceptance

- Encouraging her to take small steps of progress—and providing rewards for doing so

- Being consistent with limits—and not caving in—when things get rough

- Keeping as even an emotional keel as you can

- Advocating for her among people who don’t have such understanding (like wary teachers or school administrators or even neighbors and some relatives).

Excerpted from Straight Talk About ADHD in Girls: How to Help Your Daughter Thrive by Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD. New York: Guilford Press, 2022. Copyright © 2022 Stephen P. Hinshaw. Reprinted with permission of Guilford Press.

Excerpted from Straight Talk About ADHD in Girls: How to Help Your Daughter Thrive by Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD. New York: Guilford Press, 2022. Copyright © 2022 Stephen P. Hinshaw. Reprinted with permission of Guilford Press. Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD, is distinguished professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is also professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and vice-chair for child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. An internationally known ADHD and stigma researcher and the author of numerous articles and books for scientists, professionals, and general readers, Dr. Hinshaw has received, among other awards, the Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award from the American Psychological Association and the Sarnat International Prize in Mental Health from the National Academy of Medicine. He was recently inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Stephen P. Hinshaw, PhD, is distinguished professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is also professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and vice-chair for child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. An internationally known ADHD and stigma researcher and the author of numerous articles and books for scientists, professionals, and general readers, Dr. Hinshaw has received, among other awards, the Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award from the American Psychological Association and the Sarnat International Prize in Mental Health from the National Academy of Medicine. He was recently inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.