Retooling Strategies for Greater Success, Part Two: The 4-Quadrant Sort

Margaret Foster, MAEd

Attention Magazine December 2025

Download PDF

Going deeper with executive function tasks that are resistant to intervention

Students come to us—parents, teachers, academic coaches, and therapists—with a range of executive functioning (EF) skills which they use to manage their academic day successfully. Whether they experience challenges managing a planner, addressing long-term assignments, social skills, or “just” getting through the day, we are there to help them with a variety of skills and strategies to help them grow and flourish. When those highly useful strategies fail to provide effective results, it’s time to dig deeper, engage more fully in terms of their “problem of practice” and together discover the very, very specific tripping points in their day.

Current research about executive training compels us to “rethink… individual differences, relevance, and engagement from a contextual framework” (Niebaum JC and Munakata Y). These researchers have gone so far as to ask in one of their most recent titles: Why doesn’t executive function training improve academic achievement?

That’s a scary question. I love scary questions.

That’s a scary question. I love scary questions.

One of my favorite exercises is to take these kinds of questions posed by new research, understand their component parts and theories, and create or remodel my strategies to realign with them. I have done just that in this series and have added a few more supporting studies to support each protocol.

But back to the question: Why doesn’t executive function training improve academic achievement?

Niebaum and Munakata’s research shows that training discrete executive functions in isolation (in games and exercises that are not embedded in the context of their school subjects or routines) do not, in fact, generalize to school success. Their report does demonstrate, however, that broader success is achieved when EF training is embedded in relevance, deeper engagement, and in a context that is unique to the student.

Specifically, they emphasized that executive functions are inherently goal-driven cognitive processes. Goals, and an individual’s motivation to achieve them, are driven by personal, historical, social, and cultural contexts. Even if interventions aimed at improving specific executive functions [in isolation] were successful, children’s decisions to engage executive functions could remain unchanged, preventing transfer to outcomes in the classroom or the real world. In addition, Ashby and Crossley (2012) describe this as building both episodic memory and procedural memory, which builds strength and automaticity over time.

Most students want to succeed in school, they want to please their teachers as well as their parents, consequently many of our usual interventions can and do succeed with simple instruction. But what if they don’t? What if the problems are more complex or too persistent? How do we reach in and help that student re-engage and find success?

There are many ways practitioners address this, but this brief series addresses three fluid strategies, or protocols, that tap into these persistent fluid problems of executive functioning and engage students. Part one in this series examined Think Alouds, a simple protocol that encourages us to step back and share an exploration of the persistent problem with the student. Part two, the 4-Quadrant Sort, clarifies and prioritizes which executive functioning challenge needs to be addressed next. Part three, Finding Flow, will focus on creating a flow chart to represent the steps, sequences, and decisions of a process like a long-term assignment.

Keep in mind that each of these short, simple protocols paired with redesigned graphic organizers have a few things in common: They will immerse us even more deeply in the student’s perception and context of their unique school life, they can untangle the most persistent problems, and most importantly, they are shared.

The 4-Quadrant Sort

In Part One we looked at how to identify a “problem of practice,” and looked at a shared protocol: Think Alouds. This shared protocol encouraged us to take a look at a student’s persistent EF challenges by walking through the day or tasks together to discover the underlying obstacle(s). This next protocol comes from a pair of occupational therapists in Australia who researched it to determine which levels of support their clients needed on their path toward independent functioning. This model works well for EF skills and can be tweaked to include Think Alouds while capturing those conversations in its unique graphic organizer.

Borrowing from an approach that grew out of cognitive psychology, a four-quadrant model was developed by a team of occupational therapists in Australia, who named it their Four-Quadrant Model of Facilitated Learning (see Greber and Rodger below) and used it to measure levels of independence for their clients during therapy. It was then remodeled into a form that addressed EF issues in a practical guide for educators and featured in full in the December 2019 issue of Attention, “You’re On Your Own!”

A powerful model, it relied on the observations and knowledge of the practitioner and provided great insight into how the student was progressing toward EF independence. For our purposes here, discussing EF tasks that have become resistant to intervention, we need to take this model one step further—we need to share it with the student in a protocol that embraces flow.

A graphic model captures this process well and can be adapted in a variety of ways, but according to the principles discussed earlier, we need to ensure that the process is goal-driven by the student, very specifically context-based, and simple enough not to interfere with the cognitive processing of the problem being addressed.

An example of the model

I was working with a college-level student who was having trouble organizing their work, managing schedules, and getting work in on time. Due to their very successful communication skills, they had negotiated an accommodation for extra time for projects, which is one of my least favorite accommodations unless absolutely necessary.

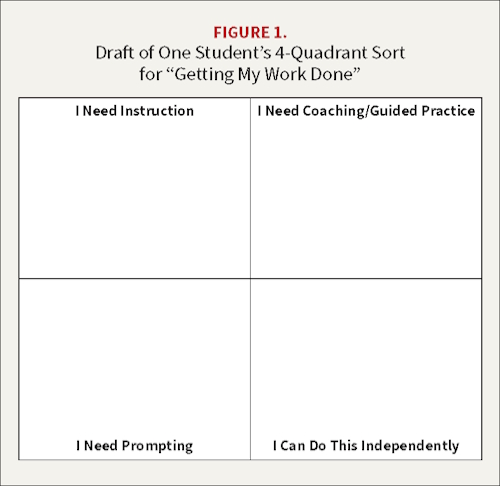

This student, who had had a very intensive IEP in high school due to a variety of spectrum features and extreme anxiety, had made incredible progress over the course of three years. At this point, the accommodation for extra time was the only one needed to help them manage task anxiety and deadlines. However, due to the inherent anxiety that late work created in them, and knowing that that would not fly in a real-world job, we were working to address this final EF task together. We drew up a modified four-quadrant model to help crystallize their understanding of Levels of Independence on a Zoom Whiteboard; see Figure 1.

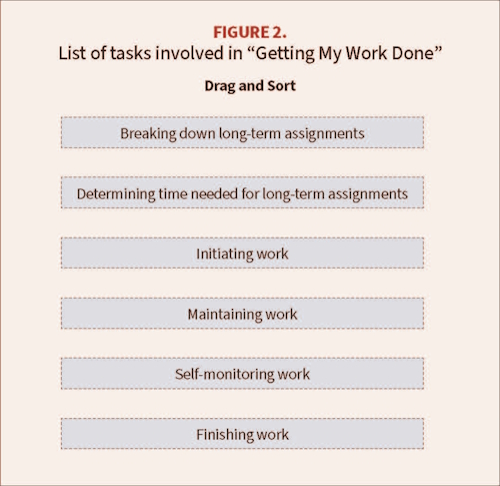

We had already identified the problem of practice together and labelled it: “Getting my work done on time.” Next, we broke that goal down into smaller EF tasks and added those in side boxes that could be slid over onto the correct quadrants; see Figure 2.

I captured some of their language using EF terminology as they had previously claimed “mastery about all things EF,” usually in order to cut off unwanted discussion with parents and others. In truth, this student knew a bit about EF, but needed more, and enjoyed crystallizing knowledge with precise vocabulary.

Finally, the student slid the boxes over to the appropriate columns and found some surprises. In the past they had pushed away help, wanting to be totally independent on all things, but once the sorting task was completed, the levels of need became clear; see Figure 3. With confidence and clarity, they declared that they would need a little help… in just a few areas. Parents would now be welcome to help with a few discreet things, but not everything! We discussed sharing this graphic with their parents to initiate a new conversation about help and independence. In addition, my role was newly clarified by the student: I would provide guidance in “Breaking down long-term assignments” and “Determining time needed.”

Another student used this protocol and discovered they were entirely independent with: Checking Assignments, Monitoring Work, and Finishing Work. They would need Guidance for Breaking Down Long-Term Assignments and Scheduling Parts. Prompts were needed for Initiating Work.

The importance of this sorting model is that it engages the student and is very specific. The tasks of sorting and prioritizing by the student provides a strong and contextualized base for increasing meaningful engagement and ultimately enhancing success with executive functions and academic achievement.

Based on my knowledge and experience with both students, they were entirely accurate with their sorting results.

Again, the importance of this sorting model is that it engages the student and is very specific. The tasks of sorting and prioritizing by the student provides a strong and contextualized base for increasing meaningful engagement and ultimately enhancing success with executive functions and academic achievement.

In our final part of the series, we will again take a problem of practice and create a dynamic plan that will help students initiate change by “Finding the Flow” needed for their individual success.

Margaret Foster, MAEd, is a learning specialist and leading consultant in the areas of executive functioning, special needs, and program development. An educational coach, former classroom teacher, and speaker at national and international conferences such as The Council for Exceptional Children, CHADD, Project Zero, and Learning and the Brain, she has trained parents, educators, and school leaders around the globe. In addition, Foster has produced numerous articles, including a special column for MedCentral and has coauthored a book, Boosting Executive Skills in the Classroom: A Practical Guide for Educators. She is a member of CHADD’s professional advisory board.

Margaret Foster, MAEd, is a learning specialist and leading consultant in the areas of executive functioning, special needs, and program development. An educational coach, former classroom teacher, and speaker at national and international conferences such as The Council for Exceptional Children, CHADD, Project Zero, and Learning and the Brain, she has trained parents, educators, and school leaders around the globe. In addition, Foster has produced numerous articles, including a special column for MedCentral and has coauthored a book, Boosting Executive Skills in the Classroom: A Practical Guide for Educators. She is a member of CHADD’s professional advisory board.

ADDITIONAL READING

Cooper-Kahn J and Foster M. Boosting Executive Skills in the Classroom: A Practical Guide for Educators. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 2013.

Foster M. You’re On Your Own: An Approach to Leading Students from Supported Instruction to Responsible Independence. Attention, December 2019.

Greber C, Ziviani J, and Rodger S. The Four-Quadrant Model of Facilitated Learning (Part 2): Strategies and Applications. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 2007, 54(Suppl.1), S41.

Niebaum JC, Munakata Y. Why doesn’t executive function training improve academic achievement? Rethinking individual differences, relevance, and engagement from a contextual framework. Journal of Cognition and Development. 2023;24(2):241-259. Epub 2022 Dec 30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2022.2160723

Other Articles in this Edition

Why Don’t Subtle Hints Work for Me?

Can AI Support Learning for Students with ADHD?

Cracking the Code on Motivation for Children with ADHD

ADHD Meltdowns: The Child’s Side of the Story and What You Should Do

Retooling Strategies for Greater Success, Part Two: The 4-Quadrant Sort

Helping Build EF Skills and Independence at Home

ADHD, Borderline Personality, and the Adolescent Girl

Remembering the Future: How ADHD Affects Prospective Memory (and How to Work with It)

I’ll Do It… Later: A Multi-Lens Approach to Understanding and Addressing Procrastination