Executive Functioning Disorder and Mathematics

Bradley Witzel

Attention Magazine October 2020

Download PDF

Three Strategies to Implement

Evan is a likeable fourth grade student who has a lot of friends but struggles in school, especially with math. He was diagnosed with ADHD last year because of his attention-related behavior. Evan thinks he understands the material, but then struggles at home with completing his homework. He feels most defeated when taking chapter and unit tests, where he struggles with knowing where to begin different multi-step problems. In many problems, Evan’s answers appear as guesses rather than the result of a systematic problem-solving approach. Evan is frustrated by the work and lost motivation. The teacher tells him that he could do the work if he just put forth more effort.

What is happening with Evan is not unlike what happens to many students with ADHD. Evan wants to perform well in mathematics, but has difficulty with multi-step problem-solving and shifting his approach from one type of problem to the next. While he wants to be successful, his lower performance has made him weary of attempts to improve, leading to a lack of effort during math. These characteristics are indicative of an issue with executive functioning (EF).

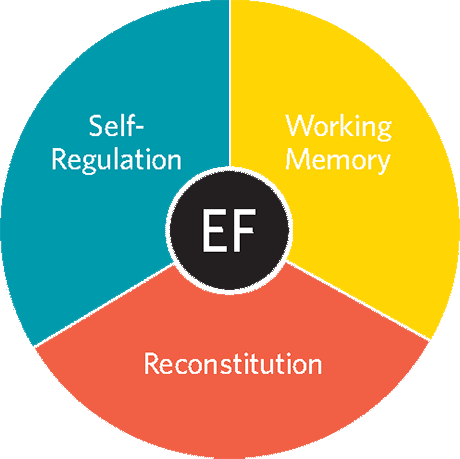

Researchers Russell Barkley, Kevin Murphy, and Mariellen Fischer found that students with ADHD often struggle with executive functioning. A student’s EF is evident in how they regulate their own learning behavior, which is critical for success in several aspects of life, including learning mathematics (Clements et al. 2016). Generally, EF involves three components: self-regulation, working memory, and reconstitution. Each of these areas impacts each other.

Self-regulation

Self-regulation appears as impulsivity within the problem-solving approach. This may manifest itself when mathematics is shown as a series of quick tricks, where content is not understood before an answer is computed. For Evan, this is particularly troublesome. As a fourth grader, math is getting more complex, particularly with word problems. In this problem (EngageNY, 2019, p. 10), Evan must analyze a word problem, develop an accurate approach, and compute the answer:

Mr. Fuller wants to put fencing around his rectangular-shaped yard. The width of the yard is 55 feet and the length is 75 feet. How many feet of fencing does Mr. Fuller need?

- 130

- 260

- 3,905

- 4,125

If Evan lacks the self-regulation to read and analyze the problem, he may see the word problem components of 55 feet and 75 feet, and also see that the answer is asking for feet. So, using his relative computational strength, he simply adds 55 + 75 to get 130. Seeing 130 as the first answer choice, A, he feels confident that he is correct. After all, what he computed shows up first in the answer choices. In this problem, Evan fails to interpret the problem as solving for perimeter because of his impulsivity in the problem-solving process.

To help students like Evan, consider providing problem-solving steps. While many approaches have been shown to help, even a three-step cognitive strategy (Say, Ask, Check) will improve students’ problem-solving and help build self-regulation (Montague, 2008).

| Say | Evan reads the problem while asking himself if he understands the information being presented. |

| Ask | Evan builds an internal dialogue through questioning himself about the information, such as “What is the question asking?” and “How do I use the information in the problem to answer the question?” Evan may even paraphrase the word problem to see if the information is presented in a manner he understands. |

| Check | Evan compares his answer to the question that was posed. |

This cognitive strategy will help Evan with self-regulation as he tackles the problem, so that he answers the problem thoughtfully rather than impulsively.

Working memory

Working memory is demonstrated by storing information, while still processing an event, so that the information is retained and can be efficiently manipulated and recalled for use at an appropriate time (Witzel, 2016). Different components of working memory serve as predictors of a student’s mathematical reasoning (Meyer, 2010). Specifically, visuospatial working memory (VSWM) impacts students’ arithmetic problem-solving approaches (Ashkenazi, 2013) and overall mathematics performance (Allen, 2019). The VSWM is like a sketchpad where students can mentally represent numbers and arithmetic, such as on a number line or through an area model. Too often, students with mathematics difficulties do not use VSWM during arithmetic problem solving (Ashkenazi, 2013). Thus, it is important to help students build mental images of mathematics in order to help students develop VSWM.

While using cognitive strategies helps students with math problem-solving, incorporating visual representations improves students’ performance (Swanson, 2015). In the same perimeter example shown earlier, Evan must be encouraged to draw a visual representation that would depict the problem solving event to help aid his VSWM.

During the Ask step, Evan should draw a visual representation to help build internal dialogue.

| 75 ft. | |

| 55 ft. |

This visual will help cue him to examine different options with which he may already be familiar (i.e., perimeter and area). By self-questioning what the problem is asking, he adjusts his visual to more easily represent a perimeter for the fence.

| 75 ft. | ||

| 55 ft. | 55 ft. | |

| 75 ft. |

During his Check within the cognitive strategy, he compares his drawing with his answer of 260 feet, helping him see the connection between the problem and his approach.

Reconstitution

Reconstitution is one’s ability to shift attention from one construct to the next and adjust to the new demands. Joswick and colleagues (2019) highlighted the importance of helping students learn to switch from one task to the next and find an appropriate and efficient strategy to tackle the new task.

In the case of Evan, he just completed a problem that required understanding and computation of perimeter. Therefore, he will be inclined to solve for perimeter with similar problems. Take for example this word problem (EngageNY, 2019, p. 11):

Ms. Peterson wants to replace all the floor tiles in her kitchen. The kitchen floor is 12 feet long and 7 feet wide. If Ms. Peterson already has 45 one-foot square tiles, how many more one-foot square tiles does she need to completely cover the kitchen floor?

Instead, Evan needs to restart his cognitive strategy. This may be difficult for a student who struggles with EF. In order to help a student switch from task to task, consider providing an organizer of prompts to initiate tasks. For this example, the teacher provides Evan an organizer of prompts that match his problem-solving cognitive strategy and Evan fills in the blanks to get started. In this example, the teacher also includes a prompt in bold to direct Evan what to do.

| What is the problem asking? | How many one-foot square tiles are still needed? | ||||||||||

| What is already given? | Length | 12 ft | |||||||||

| Width | 7 ft | ||||||||||

| Square tiles she already has | 45 | ||||||||||

| Draw your visual to match the problem |

|

||||||||||

| We need to find area. Why? |

I need to know the size of the whole floor | ||||||||||

| Then what must we do? Why? |

I subtract the number of tiles she already has. This allows me to find out how many more tiles she needs. | ||||||||||

| Calculation area 12ft x 7ft = 84ft2 84ft2 - 45ft2 = 39ft2 still needed. Ms. Peterson still needs 39 tiles. |

|||||||||||

By providing an organizer of prompts, Evan can see what he needs to solve the problem. He completes each step in the organizer before he starts his calculation. This not only helps him switch from task to task more effectively, but it also provides him cues for self-regulation and visual working memory. As Evan gains comfort with switching tasks, the teacher will reduce the number of prompts so that Evan becomes more independent over time and success.

Effective strategies help math learning

Tackling executive functioning within mathematics requires careful planning and strategy implementation to not only build the learner’s needs but also take advantage of the learner’s strengths. In the example of Evan, the teacher incorporated a cognitive strategy, visual representation, and organizer of prompts.

There are many other ways to help students with EF deficits, such as focusing content on automaticity of operational facts in order to reduce future cognitive load and employing a positive behavior approach to encourage efforts. Struggling with executive functioning does not need to stop the math learning process. Rather, it is a call for more effective strategies.

Bradley Witzel, PhD, is an award winning teacher and the Adelaide Worth Daniels Distinguished Professor of Education at Western Carolina University. As a classroom teacher, and before that as a paraeducator, he worked in multiple settings, teaching mainly math and science to high-achieving students with disabilities. Dr. Witzel has written numerous books, book chapters, and training manuals as well as several dozen research and practitioner articles. He has developed and presented six education videos and delivered over 500 workshops and conference presentations. Most importantly, he is a father of two, husband of an educator, and son of two educators.

REFERENCES AND ADDITIONAL READING

Allen, K., Higgins, S. & Adams, J. (2013). The relationship between visuospatial working memory and mathematical performance in school-aged children: a systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 509–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09470-8

Ashkenazi, S., Rosenberg-Lee, M., Metcalfe, A.W.S., Swigart, A. G., & Menon, V. (2013). Visuo–spatial working memory is an important source of domain-general vulnerability in the development of arithmetic cognition. Neuropsychologia, 51(11), 2305-2317.

Barkley, R.A., Murphy, K.R., & Fischer, M. (2008). ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. New York: Guilford Press. Clements, D.H., Sarama, J., & Germeroth, C. (2016). Learning executive function and early mathematics: Directions of causal relations. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36(3), 79–90. engageNY. (2019, June). New York state testing program. Grade 4. Mathematics Test. Released Questions. Available at https://www.engageny.org/resource/released-2019-3-8-ela-and-mathematics-state-test-questions

Joswick, C., Clements, D.H., Sarama, J., Banse, H.W., & Day-Hess, C.A. (2019). Double impact: Mathematics and executive function. Teaching Children Mathematics, 25(7), 416-426.

Montague, M. (2008). Self-regulation strategies to improve mathematical problem solving for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 31, 37–44.

Swanson, H.L., Lussier, C.M., & Orosco, M.J. (2015). Cognitive strategies, working memory, and growth in word problem solving in children with math difficulties. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(4), 339-358.

Witzel, B.S., & Little, M.E. (2016). Teaching Elementary Mathematics to Struggling Learners. New York: Guilford Press.

Other Articles in this Edition

I’m Fine, Thank You Very Much!

Supporting Successful Transition to High School

Should My Child Be Evaluated for ADHD During the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Limiting Screen Time During a Pandemic: A Guide for Parents

Balancing Virtual and Classroom Learning

Executive Functioning Disorder and Mathematics

Teaching Executive Skills in Middle School

Going to College Online with ADHD