Angels & Demons

Br. Jim Woodrum SSJE

Attention Magazine August 2021

Download PDF

I have been thinking a lot this past year about the prevalence of shame in our society. In her book Daring Greatly, self-proclaimed “shame researcher” Brené Brown defines this emotion as “the intensely painful feeling or experience of believing that we are flawed and therefore unworthy of love and belonging.” She goes on to say that we all experience shame. And, even though it is universal, we are reluctant to talk about it.[1] The insidious nature of shame insures that we dare not speak its name, giving it time to metastasize and spread throughout our lived experience.

While I cannot remember my first encounter with shame, I can recall many instances of it throughout my life; moments that have been seared into my memory by the branding iron of trauma. From being bullied by older boys in grade school to being unable to finish my college degree, shame has been a regular character in the drama of my life, lurking behind the curtain until its cue to enter and take center stage. Shame manifests in my mind like evidence presented to a jury in a court of law, which after a brief deliberation declares the devastating judgement, “You have been weighed in the balance and found wanting.”

About four years ago I began seeing a therapist, and in our initial few sessions, I recalled my experience of shame throughout the years: how I felt when my mom was called in to observe me in my third-grade classes because I was more interested in what the other kids were doing than my own work; wondering why I completed high school with a B average when I had so much trouble in math and science and often did not complete homework assignments on time in other classes; the loss of structure I experienced when I went away to college and the subsequent nosedive of my GPA, which led to me failing out of school; my three other unsuccessful attempts at finishing my degree; my difficulty with finances, relationships, and my health issues related to overeating and smoking. Questions haunted me: “Why can’t I pull my life together? What’s wrong with me?”

Vocation and diagnosis

It wasn’t the first time I’d wrestled with these questions. Back in 2004, when I was wrestling with my future direction and my past struggles, I actually found myself contemplating the prospect of joining a religious order. At first it seemed just another impulsive idea like those that from time to time would cross my mind but would never manifest into reality. However, over the next few years, the idea of becoming a monk never fully went away.

In 2012, I finally arrived at the monastery that had captured my attention eight years earlier. I thought that I had finally made it at last. From here on there would be only smooth sailing, me living a peaceful life of prayer. Though my monastic vocation was confirmed when I was life-professed in 2017, my difficulties nevertheless continued. While my exterior life may have shifted into a different mode of being, in my interior life I still had the same brain filled with the same anxieties, difficulties, and patterns of thinking.

This is how I found myself recounting the story of my life to a therapist who offered up this life-changing assessment: “Jim, it sounds to me like you may have undiagnosed ADHD. Would you be open to being tested?”

That very afternoon, I ordered a book on ADHD and devoured it. Every page seemed to tell my story, and I finally had a name and definition to the unending chaos that had followed me all my life. The questionnaires that were a part of the process revealed telltale signs of ADHD that had been present in my early childhood development and education. The battery of tests showed the different ways that ADHD was affecting my life in the present.

The diagnosis came back: ADHD, inattentive type. This official diagnosis, in a way, has facilitated my getting an “owner’s manual” for my brain. For the first time in my life, I am learning why I am predisposed to certain kinds of thinking. Learning about an ADHD nervous system has helped to give me insight about rejection sensitivity as well as my experience of “fight, flight, or freeze” when I am not in any kind of danger. I am now learning strategies to facilitate how I use my brain, especially when I feel triggered and unsafe. Above all this diagnosis has given me the courage to face the demon of my poor self-esteem and shame.

Facing the demons

My use of the word “demon” in this case is intentional. I first encountered the early Christian concept of demons when I was a novice in our community, beginning the slow two-and-a-half-year integration into the life of a monk. During that time, I took many classes on various subjects, including monastic history. One of my favorite stories I encountered was about St. Anthony, who is credited with being the first desert monk in the fourth century.

According to an early biography, Anthony left a life of comfort and privilege by travelling into the heart of the Egyptian desert to live in solitude. At first glance, you might think that Anthony just wanted to escape all of the noise and chaos of city life. But his biographer states that he did not retreat into the desert to escape life but rather to wage spiritual warfare against demons![2]

In a way I feel a sense of identification with Anthony, in that we both became monks only to find ourselves engaged in warfare against demons. We can only speculate as to what Anthony’s demons were, but I am finding that my biggest demon is something that has come to surface in the latest research in neuroscience.

There are two networks in the brain that tend to engage during different modes of activity. The Task Positive Network (TPN) lights up when we are engaged in a task and have all of our attention focused in its completion. When the TPN is doing its work, we tend to be content in working on the task before us, with little distraction from externals. When we are finished with the task, our brains transition into the Default Mode Network (DMN). The DMN is a ruminating network, which can not only make us think of good things (like a memory sparked by the smell of an apple pie baking), but can also take us into the dark space of negative rumination (such as self-criticism, the suspicion that others do not like us, and other anxieties).

In their latest book, ADHD 2.0, Edward Hallowell and John Ratey counsel that the best way to transition out of this negative place of rumination is to reengage the TPN by beginning a new task, engaging in some exercise, or even practicing mindfulness meditation. When you feel yourself slipping into a pattern of negative rumination, Hallowell and Ratey instruct: “Don’t feed the demon” (a play on the initials D-M-N of the Default Mode Network).[3]

Don’t feed the demon. It’s amazing to see how my adopted monastic heritage and the latest research into my mind’s inner workings converge in this one powerful image. As I live with this instruction on my mind, I encounter afresh the possibility of healing and wholeness, coming from two disparate sources.

My diagnosis has led me to discover a strategy that helps me to arrest those feelings of shame that would fuel suffering, and instead to move into a positive space that promotes my growth, well-being, and the fostering of healthy relationships by not allowing me to fall prey to negative rumination (which often has little basis in truth). Of all the ADHD symptoms I experience, this “demon” has done the worst damage and been the cause of many setbacks for me. But, with the help of this strategy, I have recourse and can continue to hone my skills at resisting it.

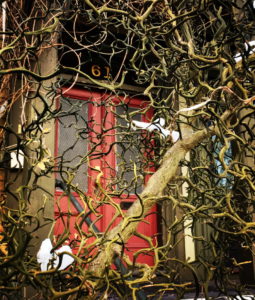

Now, when I feel that trigger of negativity beginning to course through my nervous system, I know that it is time to stop and tend to my well-being, by taking a walk, doing a chore, working a puzzle, or simply sitting down for a few minutes of mindfulness meditation, concentrating on my breathing, and recovering a sense of calm. I have even discovered a new way of prayer and mindfulness through photography. Taking photos of places and things that catch my eye, and then editing those photos in order to share the beauty I initially encountered, has been a creative and innovative way for me to foster stillness and arrest the chaos that springs from my DMN. The key is to first recognize the trigger and then find a way to transition back into the TPN.

At fifty years of age, I am now three years into my life-changing ADHD diagnosis. I know that there is no cure for ADHD, and I still occasionally suffer setbacks—especially when my mind jumps into action before I have fully processed what is happening in a given situation. But above all, I find that my brakes are getting stronger. And I am discovering new things about myself that I’d never known before.

I suppose ultimately, like Anthony, I have landed exactly where I am supposed to be, in a “desert” where I can confront and heal from the damaging attacks of the demon of shame. At the same time, I am learning to celebrate how my brain is an amazing instrument that can help me to see the angels of my higher nature, and to live a fuller and more abundant life.

Br. Jim Woodrum, SSJE, is a Brother of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, a monastic order for men in the Episcopal Church. A native of Bristol, Virginia, he came to community in January of 2012. He was life-professed in June of 2017 and has served the community as Choir Brother, Vocations Brother, and Guest Brother, and currently serves as the Brother who guides Mission and Communications. Br. Jim is active as a preacher, retreat leader, and spiritual director. When he is away from his desk (and from praying in the chapel), he enjoys cooking southern cuisine, exploring different neighborhoods in Boston, and taking photographs.

Br. Jim Woodrum, SSJE, is a Brother of the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, a monastic order for men in the Episcopal Church. A native of Bristol, Virginia, he came to community in January of 2012. He was life-professed in June of 2017 and has served the community as Choir Brother, Vocations Brother, and Guest Brother, and currently serves as the Brother who guides Mission and Communications. Br. Jim is active as a preacher, retreat leader, and spiritual director. When he is away from his desk (and from praying in the chapel), he enjoys cooking southern cuisine, exploring different neighborhoods in Boston, and taking photographs.

NOTES

[1] Brown Brené. Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent and Lead. Avery, 2015.

[2] Athanasius. “Life of St. Anthony.” Edited by Kevin Knight. Translated by H. Ellershaw, Church Fathers: Life of St. Anthony (Athanasius), New Advent, 2017, www.newadvent.org/fathers/2811.htm.

[3] Hallowell, Edward M., and John J. Ratey. ADHD 2.0: New Science and Essential Strategies for Thriving with Distraction—from Childhood through Adulthood. Ballantine Books, 2021.

CAPTIONS (from top of page)

All photography by Br. Jim Woodrum, SSJE, and used by permission.

1. Detail of Sixty-One: Cambridge, Massachusetts

2. Canterbury Ceiling: Vaulting on ceiling of Canterbury Cathedral, United Kingdom

3. Weathered Path Solo: Central Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts

4. Focus: Canterbury Cathedral, United Kingdom

5. Canterbury Distance: Canterbury Cathedral from distance, United Kingdom

6. Cave Pan: Cliff Cave near the Mar Saba Monastery, Kidron Valley, Bethlehem Governorate, West Bank

7. Sixty-One: Cambridge, Massachusetts

Other Articles in this Edition

I-PCIT: When Help Is Needed Now

ADHD and Healthy Lifestyle Behavior

Coping with and Recovering from the Pandemic: Key School Issues for Kids with ADHD

Calling All Students, We Need You!

Tracking Homework Assignments: Why Students with ADHD Struggle

The Gender Myths

(Or “Only Boys Have ADHD”)

The Myth of ADHD Overdiagnosis

The Parent As If They Are Younger Myth