ADHD in Relationships: Finding Intimacy When the World Feels Very Different

Jonathan Hassall and Kate Barrett

Download PDF

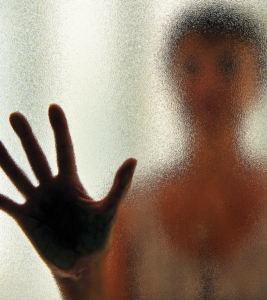

A relationshiP IS ALL ABOUT CONNECTION based on shared experiences that solidify and deepen that connection. A feature of this connection is the formation and strengthening of intimacy between the partners. But what happens when that connection is hindered by miscommunication and misunderstanding? The connection falters due to each partner feeling less understood and less able to understand the other’s intentions. This loss of connection leads to a virtual wall forming between the partners as they become increasingly uncomfortable sharing thoughts, emotions, and physical space with one another. This sense of isolation from each other supports each individual’s own assumptions, which in turn usurp opportunities for shared experiences, growth through understanding, and an appreciation for their partner’s unique strengths and values.

A relationshiP IS ALL ABOUT CONNECTION based on shared experiences that solidify and deepen that connection. A feature of this connection is the formation and strengthening of intimacy between the partners. But what happens when that connection is hindered by miscommunication and misunderstanding? The connection falters due to each partner feeling less understood and less able to understand the other’s intentions. This loss of connection leads to a virtual wall forming between the partners as they become increasingly uncomfortable sharing thoughts, emotions, and physical space with one another. This sense of isolation from each other supports each individual’s own assumptions, which in turn usurp opportunities for shared experiences, growth through understanding, and an appreciation for their partner’s unique strengths and values.

When ADHD is present, it can be easy to fall into this isolation as there are fundamental differences in how each partner perceives and experiences life. This highlights the importance of finding a way to navigate these differences in perception, approach, and experience, all of which are critical to building connection and greater intimacy. Understanding how this shift in connection presents is an important first awareness.

When a partner has ADHD and the relationship falters, the traits that originally drew the partners to each other may have become problematic. Other traits such as reliability and accountability can also be thrown into question, thereby undermining trust or even defaulting to parent-child behaviors that perpetuate a negative cycle of arguing and highlighting a power struggle within the partnership. This can lead to coexisting in a constant state of misunderstanding, compensating for perceived weaknesses or worse, poor intent.

Defaulting to negative stereotypes in times of stress, the spontaneous comedian now seems more like a scattered, insensitive clown. The cruise director may now seem like more of a taskmaster. Adjectives like disorganized, stubborn, emotional, irrational, inflexible, confrontational, irresponsible, and lazy become commonplace and only serve to erode communication channels. They are, in essence, living less like partners in crime and more often like roommates with rings. So how do they start to shift back to connection and intimacy?

First, it is critical that both partners understand and acknowledge that neither the relationship (we) nor the individual with ADHD are defined only by ADHD. Neither is every feature related to ADHD negative. Included among these are spontaneous, curious, adventurous, creative, driven, passionate, dogged problem-solver, or curator of fun—all of which offer many opportunities for positive contributions to a relationship.

While it is important to recognize how ADHD may impact relationships and individuals, it is important to remember that each of us is whole and capable of finding a way to connect and create an intimate partnership. While there are multiple common presentations to consider when one partner has ADHD, in this article, we will focus on building intimacy in the presence of ADHD.

Connection and intimacy

As mentioned earlier, connection issues in a relationship will undermine intimacy. In a relationship where ADHD is present this can be due to the difference in how each partner experiences and perceives the world (and each other). Intimacy is built upon a foundation of trust and openness to each other’s independent experience and perceptions. This practice reawakens fun, novelty, interest, connection, and passion by creating the shared experiences and understanding critical to the healthy a relationship.

In order to build and maintain intimacy, partners must feel emotionally connected, autonomous, respected, invested, and understood. In a relationship where ADHD is present, these can seem vague and difficult to achieve and maintain. Combined with the “in the moment,” inconsistent self-regulation and challenges with the need for establishing systems for building and maintaining these aspects of a relationship, it is not surprising that couples where at least one has ADHD can struggle. Creating stability in self-regulation and systems can better support the desired outcome, which is greater intimacy between partners.

To direct change, there needs to be a destination. Rather than focusing on the differences in how we each experience the world, we can directly engage in different forms of intimacy to both begin to accommodate each other’s unique perspective and build understanding. To foster intimacy, it is important to first identify the opportunities for intimacy: cognitive, experiential, emotional, and physical intimacy.

● Cognitive intimacy encompasses the practice of sharing how we think about things and is critical to help partners develop an awareness of each other’s intentions and future actions. The perceived values, fears, anticipation, and expectations help our partners understand how we engage with and understand the world.For partners with ADHD, self-regulation of emotions and attention is often challenging and different from their non-ADHD partners. It is common for partners with ADHD to rely upon thinking out loud (verbal processing) when working through scenarios or thoughts. This means that the first ideas they share might be neither fully formed nor what they intend to be the final meaning.For couples where ADHD is present, it is important to be conscious of these differences in communication approaches and to allow time for the words to coalesce into concrete intent. Equally, the partner with ADHD must address attention and impulse control challenges to allow their partner time to process, formulate, and fully explain their ideas and intentions.

● Experiential intimacy is the sharing of experiences together. Building a shared catalog of memories and connections, experiences are an opportunity to create a shared history complete with insights into each other’s emotional and intellectual experience of those moments.The attentional and emotional self-regulation challenges that can exist for partners with ADHD can interfere with experiential intimacy in several ways. First, the partner with ADHD may be distracted within the experience, missing the moment together. Alternatively, they may also be very present in a moment and struggle with the non-ADHD partner’s eagerness to move on from that moment, preferring to “sit” in the moment and take time to notice their experience of it. This inconsistency highlights the variances in preference and focus that exist for ADHD. Finally, while people with ADHD are very externally focused, they may struggle to be present for their partner’s experience of a moment, leaving the partner feeling alone or left out of the experience of the moment.The opportunity of practicing experiential intimacy is to consciously nominate moments for experience and reflection. The practice of building in communication that opens an awareness of consideration for your partner’s views within a specific experience creates greater understanding of the experience for each person.

● Emotional intimacy describes sharing how we feel and interpret emotions, which, in turn, creates emotional security and feelings of support between partners. This aspect of intimacy is critical for any close relationship as it directly impacts both cognitive and experiential intimacy. If partners feel safe enough emotionally to share how they are feeling and what is triggering that feeling in them, then they can work through their emotional experiences as a couple. This means that each partner is available to feeling emotionally safe and validated. To achieve this state, we need effective and reliable emotional self-regulation. The inherent challenges with emotional self-regulation frequently lead to misinterpretation or arguments followed by shame and guilt. Both partners can easily fall into patterns of emotionally reactive, escalating behaviors that they have unknowingly trained in each other.It is critical in a relationship where ADHD exists to address both the challenges with emotional self-regulation and reactive learned behaviors. Partners with ADHD can become expert in recognizing their emotional regulation challenges and contributing factors such as fatigue and emotional triggers. Both partners can identify patterns of reactive responses and together solve and change the patterns, often by choosing to not react but instead have a pre-planned response. In consciously addressing these issues and creating planned responses, partners can provide the space to process emotions and thereby strengthening their connections based upon emotional security and empathy.

● Last, but in no way least, is physical intimacy. Sharing close physical space can include sexual and non-sexual physical touch and proximity. Physical intimacy can be as simple as sharing space together in a room or holding hands. It can be as intense as a shared embrace or physically intimate moments often reserved for the bedroom. Whatever the level of physical connection, sharing space comfortably creates a spatial awareness of others that builds upon body language, physical presence and connection. Lack of physical intimacy can often leave partners feeling disconnected in solitude.

Intention and shared intimacy

Each of these potential types of intimacy can happen alone or in combination. However they occur, intimacy must be intentionally created, particularly if your relationship is fragile or under threat.

With ADHD, projection of planned future actions can be challenging, so it is important to be aware that for both partners the intent to act intimately must be actively anticipated and planned. A simple strategy for more effective intimate experiences is to think through:

- Who do I want to be and who do I want to support my partner to be?

- What aspect/s of intimacy do we want to explore?

- How can we engage with this type of intimacy?

- When is the best time to do it? (Keeping in mind the best time is the time you both choose!).

Within each of these intimacy perspectives, the following six components of shared intimacy can guide our actions. We must:

- TRUST that our partners come to the experience with good intentions, being capable and whole and desire a connection.

- BE WILLING to participate and explore with our partners establishing a common ground for boundaries and being open to explore unfamiliar experiences.

- BE AWARE of ourselves and our partners in how either are experiencing the moment, maintaining consideration of each other’s values, strengths, and challenges.

- ACCEPT that our partner may differ in their perceived experience, goals, or abilities in the moment and that this is okay.

- COMMUNICATE to share, collaborate, refine, and define an experience with our partners. Knowing our partners’ preferences for communication and finding a rhythm in their mannerisms, body language, tone of speech can be game changers for effective communication.

- CREATE BEHAVIORS to deliver any of the aforementioned intended outcomes. We must choose the behaviors that will deliver the intended results, or in other words, we must self-regulate our thoughts in order to determine the necessary actions to achieve future success. (Note that this IS the definition for executive functioning). Often, we know who we want to be and what we should do; the difference is in noticing what is happening and how we need to change to get a better outcome. This only delivers through planned, intentional actions. In the end, it is our actions that speak loudly to a partner.

The challenges with relationships where ADHD is present includes both inconsistent self-regulation in the moment and incomplete or absent systems for achieving and managing life systems and relationships. In finding a destination for our intent, partners may note both the perspectives of and the components that characterize intimacy.

With clear intent, we can design actions that will deliver the intimacy both partners seek. It is through this understanding of the inconsistencies of self-regulation that we can begin to address the challenges that ADHD presents and then begin to promote the aspects that add fuel to our intimate relationships.

Jonathan Hassall, BN, ACC, is an ADHD and executive function coach and director of Connect ADHD Coaching, providing services internationally from Brisbane, Australia. His background includes nursing in psychiatric services and serving as an ADHD expert in the pharmacological industry. As an active member of national and international professional ADHD associations, he provides individual and group programs and speaks regularly to professionals, community, and industry. Hassall’s focus is to translate EF theory to ADHD coaching, helping individuals with ADHD find and accept their “neuronative” state, creating effective adaptation of environment and self.

Kate Barrett, ACG, ACC, is an ADHD and executive function coach and founder of Coaching Cville in Charlottesville, Virginia. Her practice focuses on the creation of scaffolding and supports for those with ADHD. She finds teaching and coaching non-ADHD caregivers and partners further supports all members of the relationship. Her background includes a career in executive management, extensive volunteer and advocacy roles in the public school system, and ADHD expert roles in education seminars, including CHADD’s Parent to Parent and ImpactADHD’s Sanity School Live. She is a cofounder of ADHDyou’s College and Couples Programs. Barrett facilitates individual and group programs and speaks regularly to professional, community, and industry audiences.

Other Articles in this Edition

Virtual Support Groups for Adults with ADHD

A Week in the Pandemic Life of Complex Families

How Can We Help Children with ADHD Get a Better Night’s Sleep?

Keep Up Academic Skills During This Challenging Time

After It’s Over: The Pandemic’s Secondary Effects on Mental Health

ADHD, Productivity, and Working from Home

How Do You Work from Home and Help Kids Navigate Remote Learning?

ADHD in Relationships: Finding Intimacy When the World Feels Very Different