Homework Problems & ADHD?

Joshua Langberg PhD

Download PDF

Use Research-Based Strategies that Work

PROBLEMS WITH HOMEWORK COMPLETION are the most common and frustrating challenge faced by parents and teachers of children with ADHD. These children may perform well on tests but receive low or failing grades due to incomplete or missing assignments. Homework problems prevent students with ADHD from reaching their full academic potential and from displaying their true ability.

Unfortunately, homework problems also tend to be a leading cause of conflict and disagreement between parents and their children with ADHD. They often argue about what work teachers assigned, when work is due, and how much time and effort to devote to completing work and studying. Perhaps most frustrating is when parents spend hours working on homework with their children, only to learn that the assignment was lost or misplaced and not turned in the next day.

Fortunately, the acknowledgement that homework is a major concern has led to a great deal of research on developing effective strategies to address homework problems. This article will review the strategies and some of the science supporting them. If you are interested in reading more about the research, including how these strategies were developed and tested, references are provided at the end.

STEP 1: Choose one or two specific behaviors to work on.

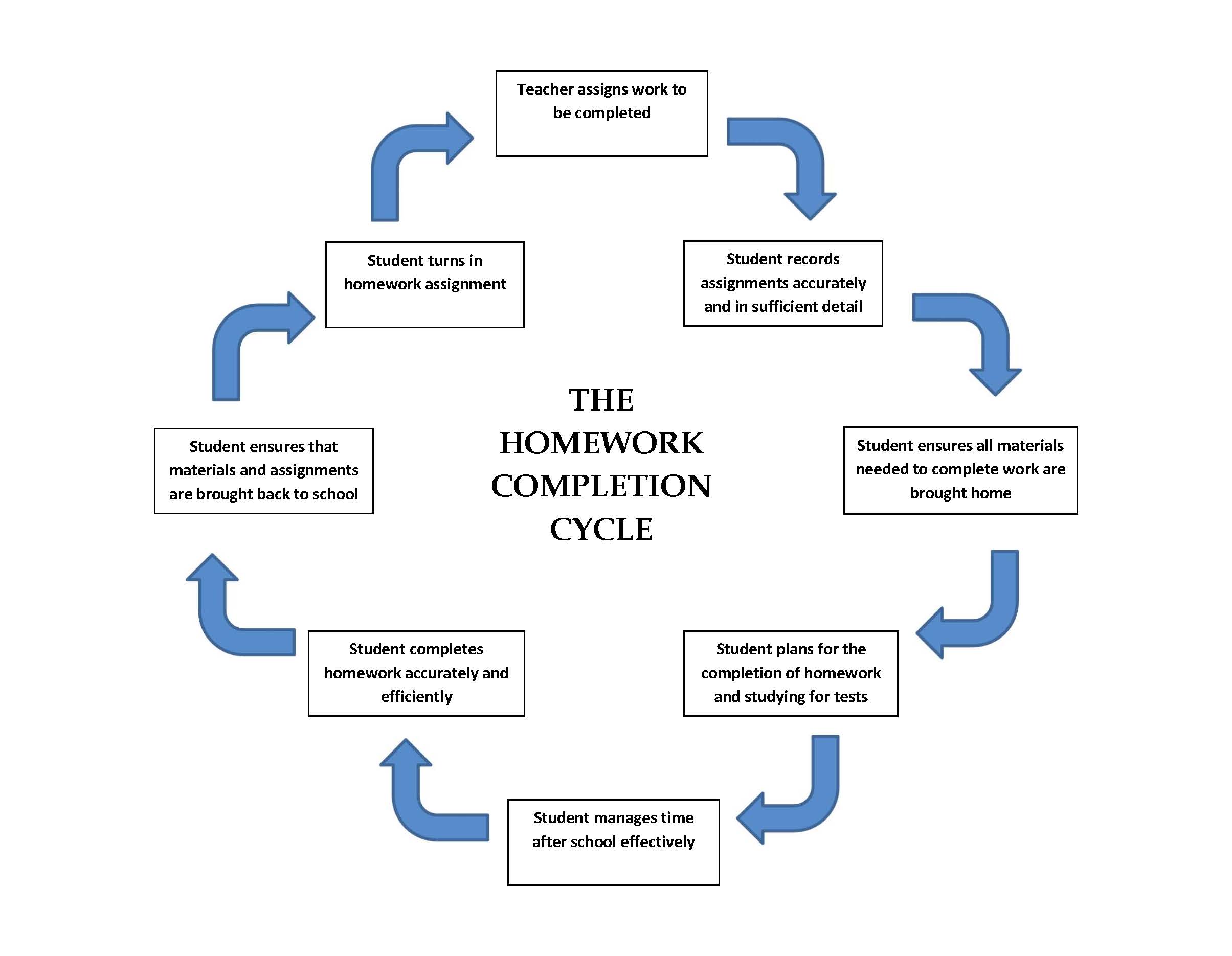

The homework completion process is fairly complex. It requires students to use organization, time-management, and planning skills and to maintain focus and attention to complete work. Let’s take a minute to think about the specific steps a child has to complete to successfully turn in an assignment, with the goal of beginning to identify where you might want to focus your intervention efforts.

● First, the child has to know what was assigned in order to complete work. Sometimes, this information is provided online and therefore, this step does not cause problems. However, in many schools, children are required to write down homework in a planner when the teacher gives the information verbally or to copy the assignment off of the board. Many children with ADHD may forget to record the assignment or may purposefully avoid writing it down.

● Second, once children know what was assigned, they have to bring the necessary materials home to complete the work. This step is where organization of materials comes into play, as many children with ADHD have disorganized bookbags and binders which causes them to lose work or to leave materials at school or home.

● Third, children have to plan out when they are going to complete work, making sure that they leave adequate time to complete work carefully and don’t procrastinate. In other words, the child has to display time-management and planning skills.

● Finally, the child has to be able to sit and actually complete the work—and focusing attention for extended periods of time on academic tasks is incredibly challenging for children with ADHD.

Unfortunately, it is not feasible to address all potential homework problems at once, as doing so will lead to a complex system and unrealistic goals. It is important to start any homework intervention effort by picking one or two of the most problematic behaviors to focus on. This can be frustrating for parents and teachers as the pace of progress seems slow. However, taking on too much at once greatly increases the likelihood that the child will not be successful. When this happens, children lose motivation to pursue academic-related goals and may begin to have negative thoughts about their ability to be successful. For these reasons, it is critical that intervention efforts start small and build only when the child has had success.

STEP 2: Clearly define what you want the child to do.

Once you have chosen what to focus on, it is critical that you define that behavior in the positive, clearly specifying what you want to see, rather than focusing on what you don’t want to see. When it comes to school, we often focus on the negative (disorganization, missing assignments, and procrastination), rather than being clear about what specific behaviors we would like the child to display.

Children with ADHD are frequently told that they are disorganized and procrastinate too often. Reiterating that message will not help them be successful. That said, defining what you want to see can be challenging. If you are focusing on organization, what does “get organized” mean? If you are focusing on time management, what does “you need to do a better job planning ahead” mean? Here are some examples to consider, but there are many additional options.

● For organization, you might specify that you want the child to “have no loose papers in their binder or book-bag” and that you want them to “use a homework folder and have only homework to be brought home or turned in located in that folder.”

● For time management, you might specify that you want your child to “write out a study plan for all tests.” You might specify that you want the study plan to include when the test is, when he or she will study, for how long, and using what method (such as flash cards, etc.).

● When addressing focus and attention during homework, consider defining what you want to see by setting work completion goals. It is challenging to define what it means to be on-task and focused. Instead, you could say that you would like to see the child “complete at least twenty problems in the next thirty minutes and get at least fifteen of them correct.”

The key here is that in each example, you can clearly determine whether or not the child complied and met the stated goal. In contrast, you can’t do that if you tell the child to “get more organized.” When you are not crystal clear about what you want to see, that vagueness often leads to conflict and disagreement about whether goals tasks were accomplished.

STEP 3: Set a clear, realistic, and achievable goal.

Unfortunately, children with ADHD learn through experience that they often do not accomplish the goals adults set for them. This results in low motivation to try and reach future goals. The only way to combat this is to show children that this time is different, and that they can and will be successful. In order to do this, you need to take into consideration where the child is starting, or their current level of the behavior. For example, it is not reasonable to expect a child to go from recording homework for zero classes to recording homework accurately for all classes. Start small, with setting a goal of accurately recording for at least one class to help motivate the child by showing them that they can succeed. It is also important to set short-term goals (daily) rather than long-term goals (weekly or longer).

For example, let’s say you tell a child that if all homework assignments are recorded accurately during the week, the family will go out to dinner to celebrate. This seems reasonable, but a child who makes a mistake on the first or second day then has no motivation to continue trying the rest of the week (the goal is now out of reach). In contrast, if the goal is a daily (assignment recording is checked each day aft er school) and the child makes a mistake, you can simply respond, “Don’t worry about it, recording assignments can be difficult to remember, I am sure you will get them all tomorrow.” In this scenario, the child’s motivation to continue trying is hopefully maintained.

STEP 4: Establish rewards if needed to help motivate the child.

As noted earlier, children with ADHD often struggle with motivation. This is partly the nature of the disorder, and partly learned life experience (“why try if experience tells me I will just fail”). When children lack internal motivation to meet goals set by parents and teachers, it can be important to make external rewards available, until the child sees that they can have success and internal motivation takes over.

These rewards don’t have to be material items that you buy. The best rewards are typically privileges children already have access to on a daily basis. For example, television or videogame time can be earned daily as a reward (for example, thirty minutes of screen time each day after school when at least three out of four assignments are recorded correctly).

Try to get creative with reward options. For example, the child could earn such privileges or activities as going to bed thirty minutes later than usual, being read to by a parent for an additional twenty minutes, choosing what is for dinner, or a get-out-of-walking-the-dog pass. It is important to be clear that material rewards are not always needed. Some children are motivated to achieve goals simply for the opportunity to receive verbal praise from parents and teachers.

FOUR STEPS TO SUCCESSFUL HOMEWORK INTERVENTION

1. Pick one or two specific homework behaviors to focus on first.

2. Carefully define what you want to see the child do.

3. Set clear, realistic, and achievable goals; short-term (daily) goals work best.

4. Identify a privilege-based reward that the child can earn for goal achievement.

ADDITIONAL READING

Gallagher, R., Abikoff, H.B., & Spira, E.G., Organizational Skills Training for Children with ADHD: An Empirically Supported Treatment. Guilford, 2014.

Langberg, J.M. Improving Children’s Homework, Organization, and Planning Skills (HOPS): A Parent’s Guide. Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists Publications, 2014.

Power, T.J., Karustis, J.L., & Habboushe, D.F. Homework Success for Children with ADHD: A Family–School Intervention Program. New York, NY: Guilford, 2001.

If you’re interested in reading research articles on the evaluation of the strategies, see:

Evans, S.W., Langberg, J.M., Schultz, B.K., Vaughn, A., Altaye, M., Marshall, S.A. & Zoromski, A.K., (2016). Evaluation of a school-based treatment program for young adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(1), 15-30.

Langberg, J. M., Dvorsky, M. R., Molitor, S. J., Bourchtein, E., Eddy, L. D., Smith, Z. R. . . . & Eadeh, H. M. (2018). Overcoming the research-to-practice gap: A randomized trial with two brief homework and organization interventions for students with ADHD as implemented by school mental health providers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(1), 39.

Merrill, B. M., Morrow, A. S., Altszuler, A. R., Macphee, F. L., Gnagy, E. M., Greiner, A. R., . . . & Pelham, W. E. (2017). Improving homework performance among children with ADHD: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(2), 111.

Pfiffner, L. J., Rooney, M., Haack, L., Villodas, M., Delucchi, K., & McBurnett, K. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of a school-implemented school– home intervention for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and impairment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(9), 762-770.

Power, T. J., Mautone, J. A., Soffer, S. L., Clarke, A. T., Marshall, S. A., Sharman, J., . . Jawad, A. F. (2012). A family-school intervention for children with ADHD: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 611–623.

Sibley, M. H., Graziano, P. A., Kuriyan, A. B., Coxe, S., Pelham, W. E., Rodriguez, L. . . . & Ward, A. (2016). Parent–teen behavior therapy + motivational interviewing for adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 699.

Joshua M. Langberg, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and associate professor of psychology at Virginia Common wealth University. At VCU, he directs the child/adolescent concentration of the clinical psychology program and the Promoting Adolescent School Success (PASS) research group, and co-directs the Center for ADHD Research, Service, and Education. He developed the Homework, Organization, and Planning Skills intervention and published the HOPS treatment manual and a companion guide for parents.